Scroll to:

AGE AND COMPOSITION OF EOCENE SANDSTONES IN WESTERN KAMCHATKA: APPLICATION TO THE STUDY OF PROVENANCE FOR PETROLEUM RESERVOIRS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK

https://doi.org/10.5800/GT-2025-16-5-0852

EDN: falzbc

Abstract

The lithology, composition, U-Pb LA-ICP-MS ages of detrital zircons from sediments of the Western Kamchatka Basin (Russian Far East) provide important insight into paleogeography and tectonic setting of the Sea of Okhotsk in the Eocene. Our study is based on mapping, structural observations, descriptions of the sections and lithology, composition of the sandstones, and U-Pb LA-ICP-MS dating and morphology analysis of detrital zircons from the Eocene sandstones of the Western Kamchatka Basin. The provenance for the sandstones is mainly associated with orogen recycling in magmatic arcs. The analysis of heavy minerals indicates mafic to sialic sources. The mafic terranes of the Asian margin on the west or/and Olyutorka-Kamchatka ensimatic island arc affected the mechanism transferring the basic material to the Western Kamchatka Basin in the Eocene. The sialic clasts originated from continental blocks of the Asian margin and the Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt.

New data allow us to prove that the erosion of the Okhotsk-Chukotka belt had a significant influence on the sedimentation system in the north of the Sea of Okhotsk in the Eocene. We can assume that the Paleo-Penzhina River system already existed in the Eocene. The existence of the sialic sources in Eocene allows us to assume the possibility of finding the good quality collectors in the Eocene deposits of the Western Kamchatka Basin and the north of the Sea of Okhotsk.

Keywords

For citations:

Soloviev A.V., Khisamutdinova A.I., Hourigan J.K., Akinin V.V., Levochskaya D.V. AGE AND COMPOSITION OF EOCENE SANDSTONES IN WESTERN KAMCHATKA: APPLICATION TO THE STUDY OF PROVENANCE FOR PETROLEUM RESERVOIRS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK. Geodynamics & Tectonophysics. 2025;16(5):0852. https://doi.org/10.5800/GT-2025-16-5-0852. EDN: falzbc

1. INTRODUCTION

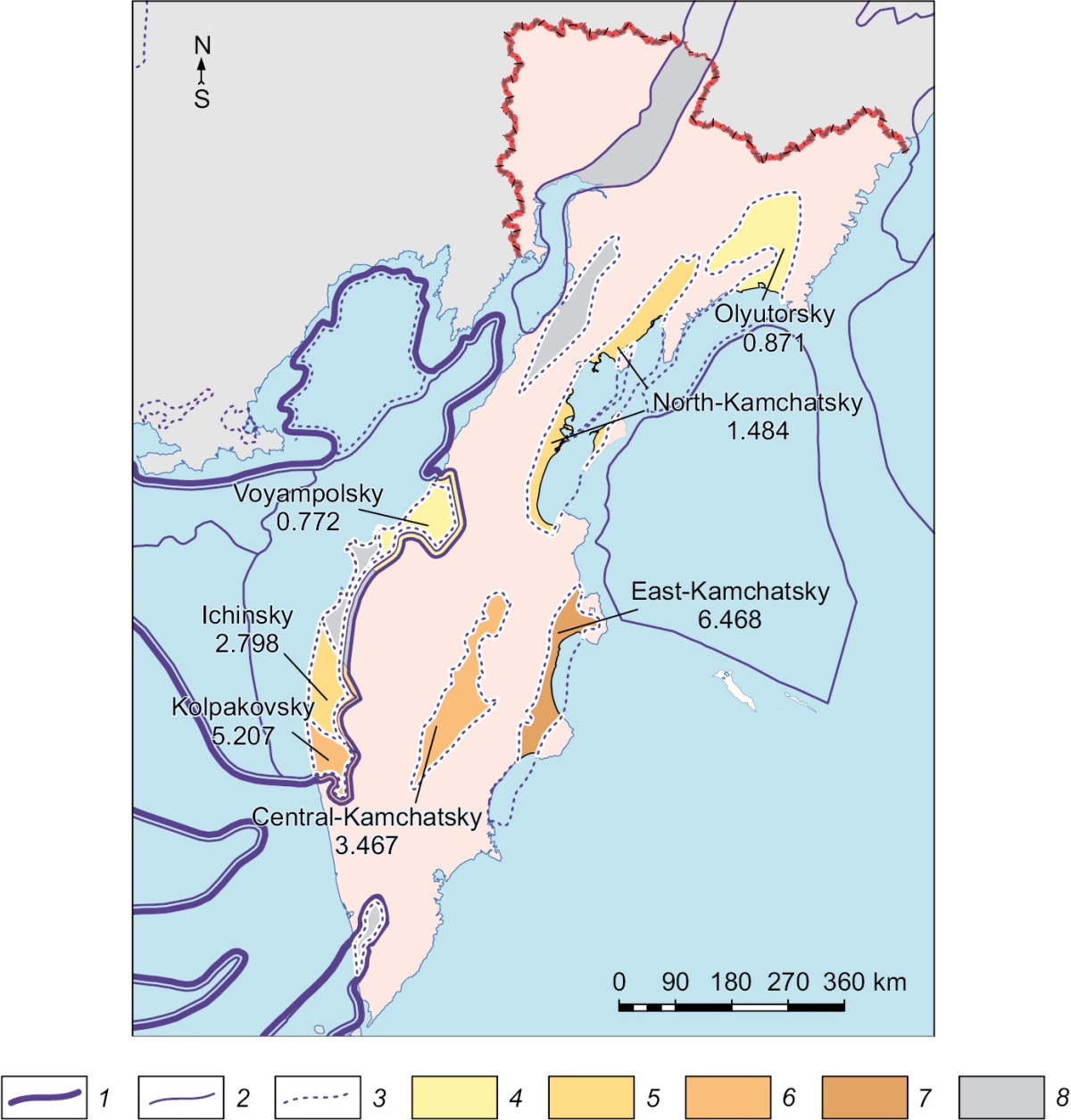

The Sea of Okhotsk is a frontier basin that has generated significant interest in the viability of petroleum systems originating and hosted within the Eocene strata [Gladenkov, 1980; Khvedchuk, 1993; Harbert et al., 2003]. Huge (14 billion barrels (1.9 billion tons) of oil and 96 trillion cubic feet (2.7 trillion cubic meters) of gas) petroleum resources in the northern Sakhalin Island have heightened interest in the petroleum potential of the Sea of Okhotsk as a whole [Kharakhinov, 2010; Khisamutdinova et al., 2018; Stoupakova et al., 2021; Kalinin et al., 2022]. In [Mel’nikov et al., 2022] the available geological and geophysical data served as a basis for making quantitative assessment of the total initial resources of the Kamchatka Krai as on 01.01.2022, which was 499.8 million tons of hydrocarbon equivalents (geological) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Density map of the total initial HC resources of the Kamchatka Region as on January 1, 2022 after [Mel’nikov et al., 2022].

Borders of oil and gas geological zoning: 1 – provinces; 2 – regions; 3 – areas. Density of total initial recoverable resources, hydrocarbon equivalents thousand t/km²: 4 – up to 1; 5 – from 1 to 3; 6 – from 3 to 6; 7 – more than 6; 8 – uncertain prospects.

Рис. 1. Карта плотности начальных ресурсов углеводородного сырья Камчатского края на 01.01.2022 г. по данным [Mel’nikov et al., 2022].

Нефтегазогеологическое районирование: 1 – провинции; 2 – районы; 3 – области. Плотность начальных суммарных извлекаемых ресурсов, в углеводородном эквиваленте тыс. т/км²: 4 – до 1; 5 – от 1 до 3; 6 – от 3 до 6; 7 – более 6; 8 – неопределенные перспективы.

A critical piece of the puzzle is the quality of the sandstone reservoir that hosts matured petroleum reserves. For instance, high-quality arkose reservoir rocks of the Sakhalin system occur within long-lived perideltaic deposits of the Amur River, which drains a vast area (~1.85M km²) of the Russian Far East comprising the evolved continental basement. The question is whether the Sakhalin Island is a unique reservoir structurally related to the Sakhalin-Hokkaido shear zone [Rozhdestvenskiy, 1982; Worrall et al., 1996] or there are other viable high-quality host-rock systems within the Okhotsk Basin. This paper interrogates sediment provenance and the paleogeography of sediment dispersal systems exposed in the Western Kamchatka as a predictive model for occurrence of reservoir quality rocks in the circum-Okhotsk region.

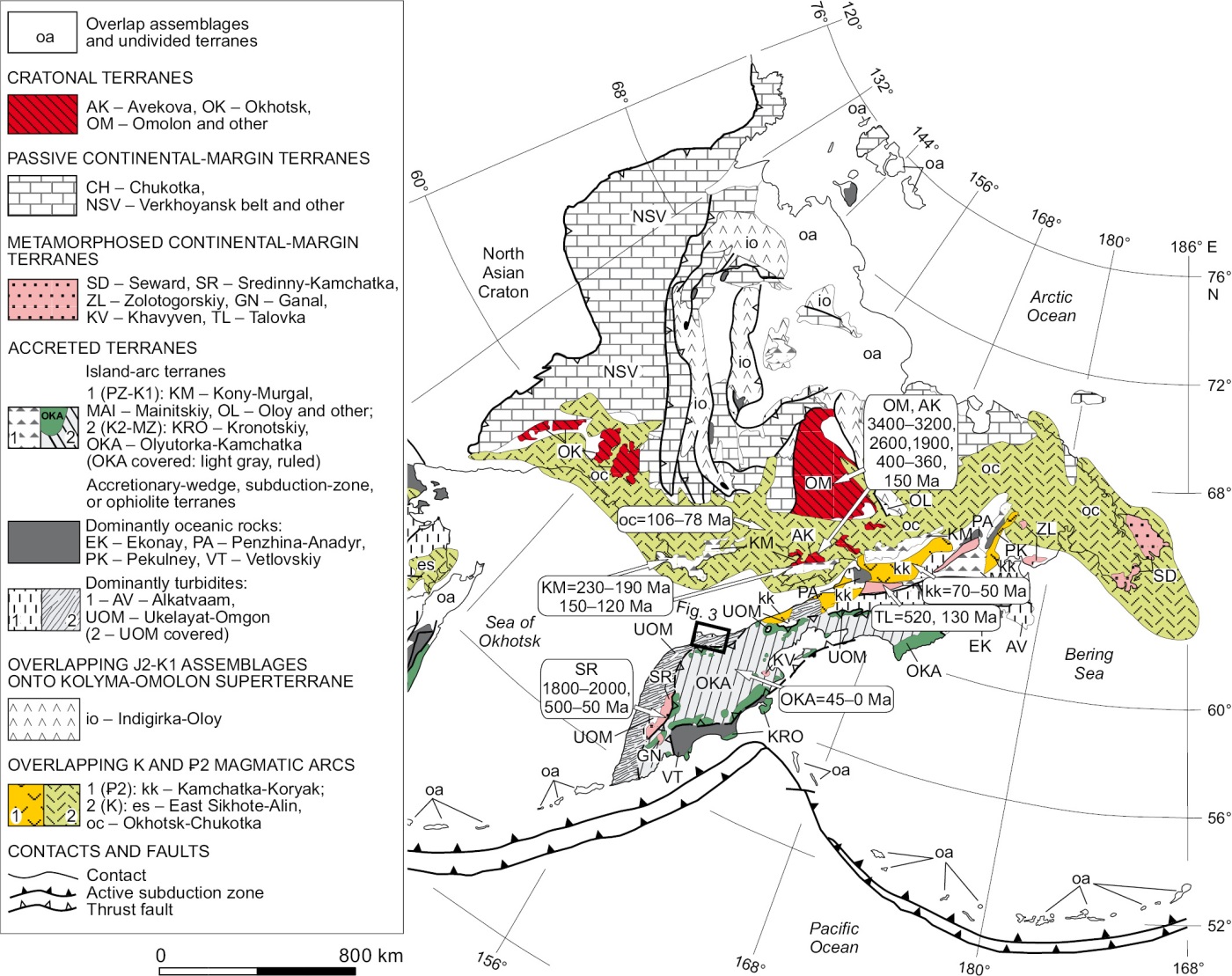

Northeast Asia includes the Paleozoic to Cenozoic oceanic and arc terranes that have been swept into the margin during the Late Jurassic to Tertiary (Fig. 2) [Nokleberg et al., 2001; Khanchuk, 2006]. A dominant geological feature along this margin is the Cretaceous Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt (OCVB), which is a prominent subduction-related magmatic province formed as a part of this terrane collage. The OCVB represents a laterally extensive Andean-style arc that persisted along the southern margin of the western and northern edge of what is now the modern boundary of the Sea of Okhotsk and Bering Shelf [Nokleberg et al., 2001]. The modern studies indicate that the Middle Albian to Early Campanian (106–77 Ma) magmatic activity in the OCVB was highly discontinuous [Akinin, Miller, 2011; Tikhomirov et al., 2012; Akinin et al., 2022]. The volcanism was terminated by the 76–78 Ma plateau basalts [Hourigan, Akinin, 2004], which mark a change in the geodynamic setting from frontal subduction to the regime of a transform margin with local extension [Akinin, Miller, 2011]. Since the Cretaceous, the OCVB has been a main mountain chain on the North-East Asian margin that shed clastic material off toward the marginal seas and the paleo-Pacific.

Fig. 2. The tectonostratigraphic terranes and overlap assemblages of the Russian Far East (modified after [Nokleberg et al., 2001; Hourigan et al., 2009]).

Рис. 2. Тектоностратиграфические террейны и перекрывающие их комплексы Дальнего Востока России (по [Nokleberg et al., 2001; Hourigan et al., 2009], с изменениями).

The Sea of Okhotsk region (Fig. 2) remains a geologic frontier. The Sea of Okhotsk is floored almost exclusively by a thin crust of debated affinity. The material dredged from bathymetric highs and the velocity structure form the basis for interpretation of basement geology of the Sea of Okhotsk. Given the paucity of direct evidence, leading models reveal significant disparities in: 1) captured oceanic plateau [Watson, Fujita, 1985; Bogdanov, Dobretsov, 2002]; 2) accreted microcontinental block [Parfenov, Natal’in, 1977; Konstantinovskaia, 2001], or 3) extended continental framework of accreted terranes [Hourigan, 2003; Schellart et al., 2003; Verzhbitsky, Kononov, 2006].

Collided-block models hold that an allochthonous microcontinent or oceanic plateau collided with the margin of northeastern Asia in the Late Cretaceous, resulting in the cessation of magmatism in the Andean-style Okhotsk-Chukotka belt [Parfenov, Natal’in, 1977; Konstantinovskaia, 2001; Bogdanov, Dobretsov, 2002]. Both [Parfenov, Natal’in, 1977; Konstantinovskaia, 2001] argued that the microcontinental block extends on land on the Kamchatka Peninsula. However, these models are inconsistent with a more recent model demonstrating the Eocene high-grade metamorphism of northeast Russia sediments within the Sredinniy Range [Hourigan et al., 2009].

An alternative view is that the Omgon-Palana belt (north and west of the Sredinniy Range) acts as a collision zone separating the Sea of Okhotsk plate from the West Kamchatka microplate. [Bogdanov, Chekhovich, 2002] argue that a fragment of an ancient oceanic plateau makes up the Sea of Okhotsk microplate, while the West Kamchatka plate is a quasi-continental crust [Bogdanov, Chekhovich, 2002].

Finally [Hourigan, 2003; Verzhbitsky, Kononov, 2006] propose a back-arc extensional model with basement geology made up of a variety of the Mesozoic terranes. [Schellart et al., 2003] assume the occurence of slab rollback based on the eastsouthward-propagating extensional zone that has progressively extended since the Eocene [Hourigan, 2003].

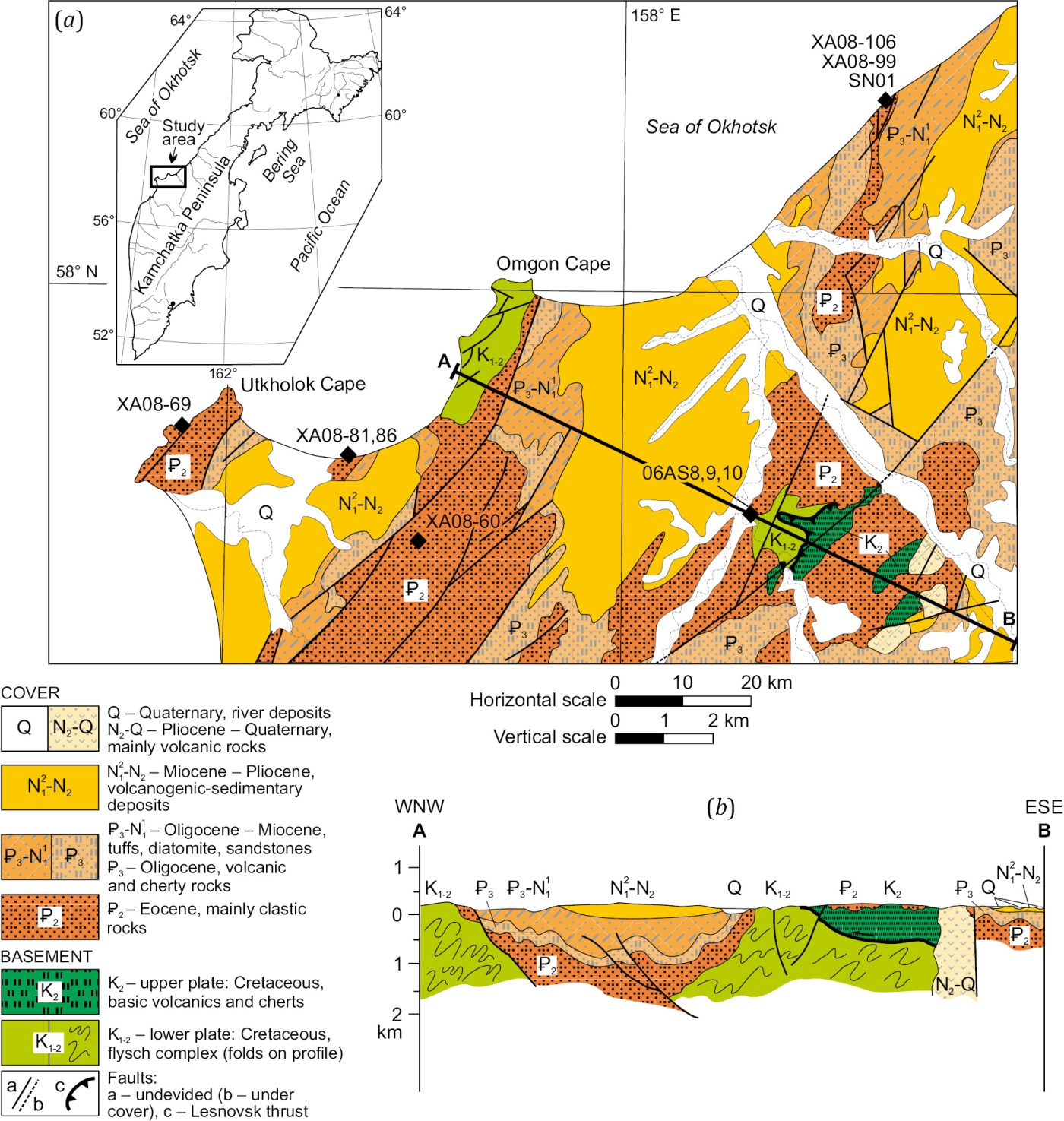

In this context, the provenance composition of the Eocene sediments in the Western Kamchatka Basin (Fig. 3) should provide insight into the Early Paleogene paleography of the Sea of Okhotsk. Each model outlined above provides a unique prediction for the composition, provenance and dispersal patterns within the Sea of Okhotsk. This study is the first to integrate mapping, structural observation, regional lithostratigraphy correlation and sandstone composition with U-Pb LA-ICP-MS provenance analysis of detrital zircons from the Eocene sandstones of the Western Kamchatka Basin.

Fig. 3. The geological map (modified after [Litvinov et al., 1999]) (a) and cross section of the Western Kamchatka study area (b). The cross section has been drawn using the unpublished seismic data obtained by PetroKamchatka Ltd. The samples under study are shown by rhombuses.

Рис. 3. Геологическая карта (по [Litvinov et al., 1999], с изменениями) (a) и разрез исследуемой территории на Западной Камчатке (b). Разрез составлен с использованием неопубликованных сейсмических данных PetroKamchatka Ltd. Образцы для исследования показаны ромбами.

2. TERRANES IN THE BASEMENT OF THE WESTERN KAMCHATKA BASIN

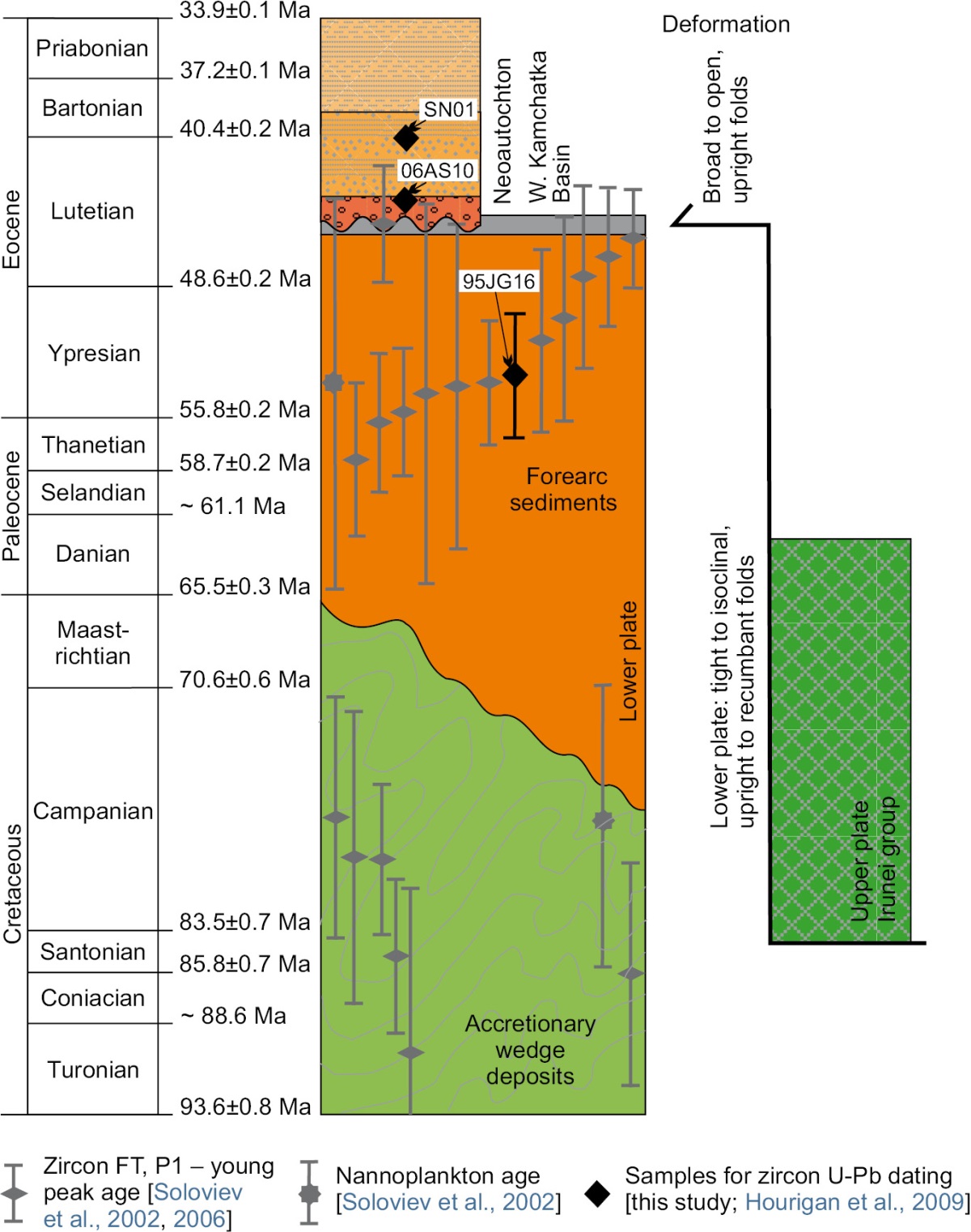

The basement of the Kamchatka can be subdivided into four terranes: Ukelayat-Omgon (UOM), Olyutorka-Kamchatka (OKA), Vetlovskiy (VT), and Kronotskiy (KRO) (see Fig. 2) [Nokleberg et al., 2001; Khanchuk, 2006]. The deposits of the Western Kamchatka Basin rest on Ukelayat-Omgon (UOM) and Olyutorka-Kamchatka (OKA) terranes [Shapiro, Soloviev, 2009]. The Ukelayat-Omgon terrane (UOM) consists of strongly deformed (tightly folded) Cretaceous – Middle Eocene continent-derived flysch-like sediments [Garver et al., 2000]. The deposits of the Ukelayat-Omgon terrane were accumulated along the continental margin of the northeast Asia. The Omgon Range of Western Kamchatka contains the Middle to Upper Cretaceous sequence of flysch with tectonic inclusions of the Jurassic – Cretaceous oceanic rocks inferred to have been imbricated together in an accretionary prism [Soloviev et al., 2006]. The accretionary prism resulted from subduction of the Pacific paleo-oceanic plate (Izanagi) under the Eurasian continental margin and was attended by volcanism in the inboard Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt. Internal imbrication was completed by the Maastrichtian (~70 Ma) as indicated by apatite fission-track ages that record cooling and exhumation of this crustal block [Soloviev et al., 2006]. The Olyutorka-Kamchatka terrane (OKA), composed of the Late Cretaceous to Paleocene basalt, chert, intermediate volcanics and associated volcanogenic sediments, has been interpreted as an island arc. The allochthonous island arc units and continental margin strata are juxtaposed along a ~1500 km-long suture zone (see Fig. 2). The northeast, central and southwest segments of this fault are referred to as the Vatyna thrust (Koryak Highlands), the Lesnovsk thrust (Lesnovsk Highlands in the Kamchatka Isthmus), and the Andrianov thrust (Sredinnyi Range), respectively [Soloviev et al., 2001; Hourigan et al., 2009]. The forearc sediments of Ukelayat-Omgon terrane were deformed in the Eocene (52–46 Ma) because of collision between the Olyutorka-Kamchatka terrane and northeastern Asian margin [Soloviev et al., 2002, 2011].

3. GEOLOGY OF THE WESTERN KAMCHATKA BASIN

The Pre-Tertiary rocks in Western Kamchatka generally occur as isolated exposures (Fig. 3) [Litvinov et al., 1999]. The Lesnovsk thrust which separated the Ukelayat-Omgon and the Olyutorka-Kamchatka terranes from each other is observed in erosional windows (Fig. 3, 4). The eastern part of the Sea of Okhotsk and the western Kamchatka Peninsula are occupied by the Western Kamchatka Basin filled with the Cenozoic sediments [Litvinov et al., 1999]. The Tertiary rocks in Western Kamchatka are poorly exposed, and the outcrops are difficult to access due to limited infrastructure. The best-described are those located along the coastal cliffs. These outcrops are most critical for understanding of the structure of the Tertiary complexes, which is, in turn, significant for interpretation of geodynamics of the Sea of Okhotsk and reliable assessment of its petroleum resource potential.

Fig. 4. The tectonostratigraphic column for the Western Kamchatka Basin: the relationship between lower plate, upper plate and cover. The stratigraphic chart is from [Ogg et al., 2008].

Рис. 4. Тектоностратиграфическая колонка Западно-Камчатского бассейна: соотношение автохтона, аллохтона и неоавтохтона. Стратиграфическая схема составлена по [Ogg et al., 2008].

The previous geological mapping revealed that the Cenozoic sequences of the Western Kamchatka Basin are deformed into simple folds with the NNE-trending axes [Geological Map…, 1965]. According to [Litvinov et al., 1999] the Tertiary sediments fill grabens and rest upon the erosional surface of the highly deformed pre-Cenozoic basement. It has been recently shown that the Tertiary sediments of western Kamchatka experienced significant fold-thrust deformations [Mazarovich et al., 2010]. The Oligocene – Lower Miocene sequences demonstrate isoclinal superposed folds, thrusts, and duplex structures characteristic of the compression regime (see Fig. 3). The last stage of strong deformations occurred in the mid-Miocene and may represent a response to termination of collision between the Eastern Peninsulas (Kronotskaya) island arc zone and the eastern Kamchatka Peninsula [Verzhbitsky, Soloviev, 2009].

[Gladenkov, 1980; Gladenkov et al., 1997] report a generalized stratigraphy of the West Kamchatka basin, marked by the Eocene – Pliocene strata overlying the Cretaceous strata, which consist mostly of deep marine turbidites and organic-rich mudstone. The Eocene part of the succession is largely nonmarine and consists of a 500 m thick fining-upward succession of predominantly coarse clastic material interbedded with coal and organic-rich shales. A 3000 m thick succession of the Upper Eocene-Oligocene sandstone, coal and shale beds in the Western Kamchatka Basin is capped by a thick, laterally widespread mudstone. The 4000–4500 m thick Miocene section with a sandstone-rich unit (>1000 m) at the base is thought to have been deposited in shallow marine shelf environments. It is overlain by an approximately 500 m thick interval of tuffaceous cherty rocks that underlie a 2000–2500 m thick sequence of interbedded sandstone, conglomerate and diatomite. The uppermost Miocene-Pliocene section consists of interbedded sandstone and coal. In the Western Kamchatka Basin, this succession consists of the Eocene – Lower Oligocene nonmarine-shallow marine sequence, overlain by the much thicker Oligocene-Upper Miocene upward-shoaling progradational slope to shelf sequence. [Oleinik, 2001] consider the Eocene-Miocene rocks as the major Miocene transgressive sequence ranging from tidal-to-shelf environments at the bottom of the section to slope facies.

Scout reports from the onshore gas-condensate fields of the Western Kamchatka Basin also place the interval of interest in the Paleogene section, unconformably overlying the Upper Cretaceous strata [Belonin et al., 2003]. The sedimentary section in these onshore areas is subdivided into five lithostratigraphic sequences: (1) the alluvial Khulgun formation; (2) the alluvial-lagoonal Napana formation; (3) the nearshore shelf Snatol formation; (4) the coastal plain Kovachin formation; (5) the deep-water shelf Kuluven and Viventek formations. We collected ten (10) sandstone samples from the lower part of the Paleogene section (Khulgun, Napana and Snatol formations). The locations of the samples under analysis and discussion are shown in Fig. 3, 4 and their exact locations and ages are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Location and age of the Eocene sandstone samples (Western Kamchatka)

Таблица 1. Места отбора образцов и информация о возрасте палеогеновых песчаников (Западная Камчатка)

|

Field number |

Latitude, N |

Longitude, E |

Map unit |

Age |

|

95JG16 |

61°41'57" |

171°47'51" |

Ukelayat group |

Early Eocene |

|

ХА08-106 |

58°16'53" |

158°42'30" |

Snatol fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

ХА08-99 |

58°16'42" |

158°42'16" |

Snatol fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

SN01 |

58°16'40" |

158°42'07" |

Snatol fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

ХА08-69 |

57°47'44" |

156°51'57" |

Cape Zubchaty fm. |

Paleocene (?) |

|

ХА08-81 |

57°46'03" |

157°19'20" |

Khulgun fm. |

Paleocene (?) |

|

ХА08-86 |

57°46'06" |

157°19'51" |

Snatol fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

ХА08-60 |

57°43'29" |

157°40'22" |

Snatol fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

06AS10 |

57°41'27" |

158°19'44" |

Napana fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

06AS09 |

57°41'26" |

158°19'48" |

Napana fm. |

Middle Eocene |

|

06AS08 |

57°41'25" |

158°19'51" |

Napana fm. |

Middle Eocene |

Note. The detrital zircons from samples highlighted bold were dated by U-Pb LA-ICP-MS method.

Примечание. Обломочные цирконы были датированы методом U-Pb LA-ICP-MS из образцов, выделенных жирным шрифтом.

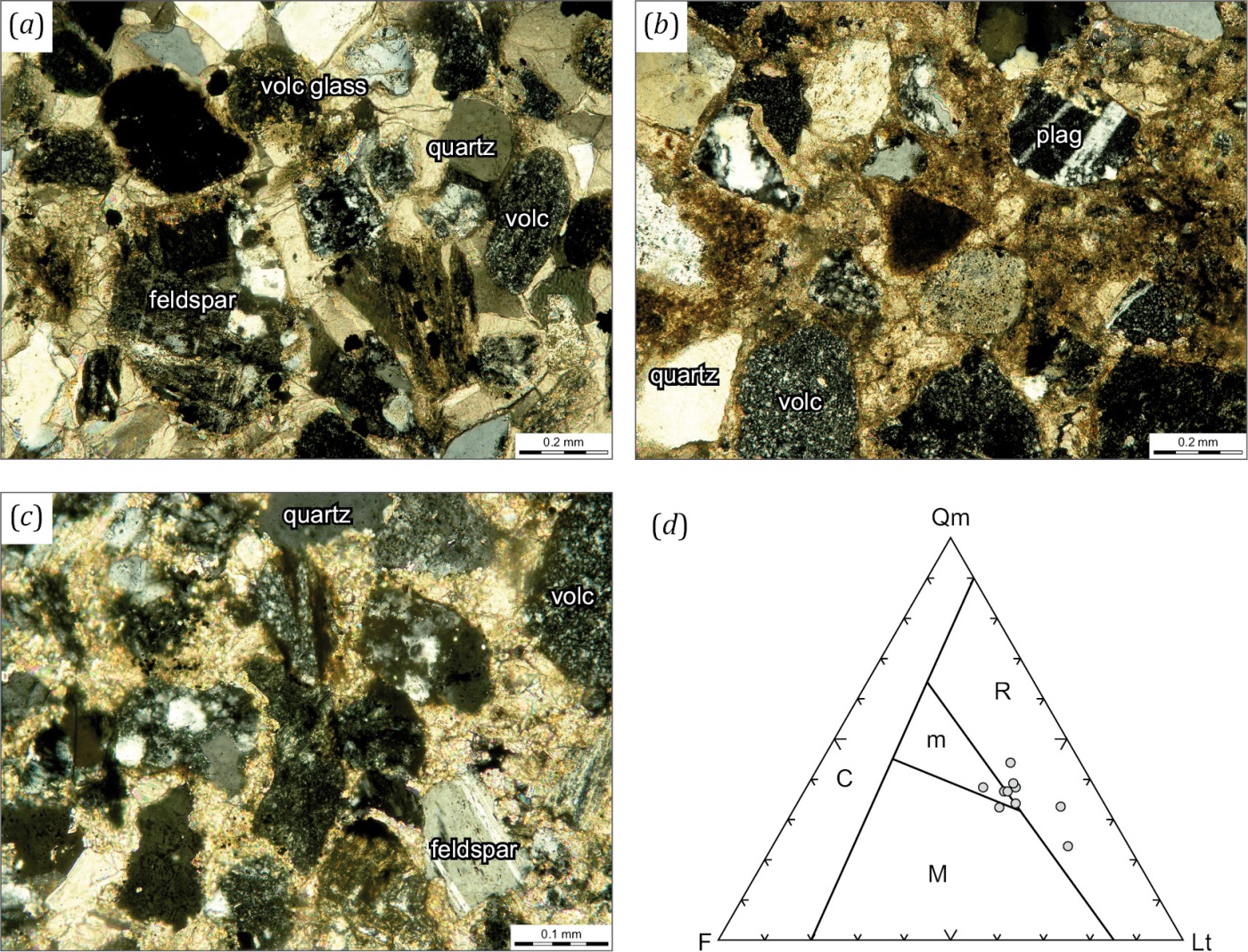

4. SANDSTONE COMPOSITION

Poorly sorted and angular to slightly rounded grains, together with quartz, plagioclase and mica point to proximal orogenic sources that contained mostly volcanic rocks and some sedimentary rocks which are present as abundant lithic fragments therein (Fig. 5; App. 1, Table 1.1, 1.2). Volcanic lithic fragments are dominated by variable amounts of mafic to felsic volcanic rocks and devitrified glasses. Sedimentary and metasedimentary rocks also form an important component of the sandstones. These are mostly fragments of siltstone, fine-grained sandstones, cherts and metaquartzites (Fig. 5; App. 1, Table 1.1). The sandstones are quartz-feldspar graywaсkes [Pettijohn, 1975] or lithic arenites [Folk et al., 1970]. The sandstones were mainly derived from orogen recycling in magmatic arcs (Fig. 5) [Dickinson, 1985].

Heavy minerals include variable percentages of zircon, apatite, rutile, leucoxene, sulphides, ilmenite, garnet, black spinel (App. 1, Table 1.3). All samples can be divided by sulfide content into high-, medium- and low-sulphide groups. According to [Pettijohn, 1975], all diagnosed minerals were divided into three groups: indicator minerals for acid rocks – zircon, apatite, rutile, tourmaline; indicator minerals for basic rocks – pyroxene, ilmenite (leucoxene), spinel; other minerals. It should be noted that pyrite dominates quantitatively in this group. An insignificant amount of garnet probably indicates the presence of high-aluminous granitoids or metamorphic rocks. It should be noted that minerals typical for metamorphic sources were not detected in samples.

Fig. 5. Photomicrographs (a–c) and point-count data (d) for the Eocene sandstones from the Western Kamchatka Basin.

(a) – sample XA08-81, x-polars; (b) – sample AS06-9, x-polars; (c) – sample XA08-106, x-polars; (d) – ternary diagram shows monocrystalline quartz (Qm), feldspar (F), total lithic (Lt) composition and provenance fields: C – continental block, R – recycled orogen, M – magmatic arc, m – mixed [Dickinson, 1985].

Рис. 5. Микрофотографии (a–c, скрещенные николи) и данные точечного подсчета (D) для эоценовых песчаников Западно-Камчатского бассейна.

(a) – образец XA08-81; (b) – образец AS06-9; (c) – образец XA08-106; (d) – треугольная диаграмма показывает состав монокристаллического кварца (Qm), полевого шпата (F), суммарного литического материала (Lt) и поля источников сноса: C – континентальный блок, R – рециклированный ороген, M – магматическая дуга, m – смешанный [Dickinson, 1985].

Obviously, there are at least two sources of erosion within the study area: acid and basic igneous rocks. Zircon and apatite are most common in sialic rocks. Basic rocks are mostly characterized by anatase, pyroxene, ilmenite, along with leucoxene, chromite and rutile. Hence, the analysis of heavy minerals indicates a mixture of materials derived from mafic and sialic sources.

5. DETRITAL ZIRCON DATA

Zircon crystals were extracted from samples by traditional methods of crushing and grinding, followed by separation with a table, heavy liquids, and a magnetic separator. Samples were processed so that all zircons were retained in the final heavy mineral fraction. The separations were made in the Laboratory of mineralogical and fission-track analysis (Geological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences).

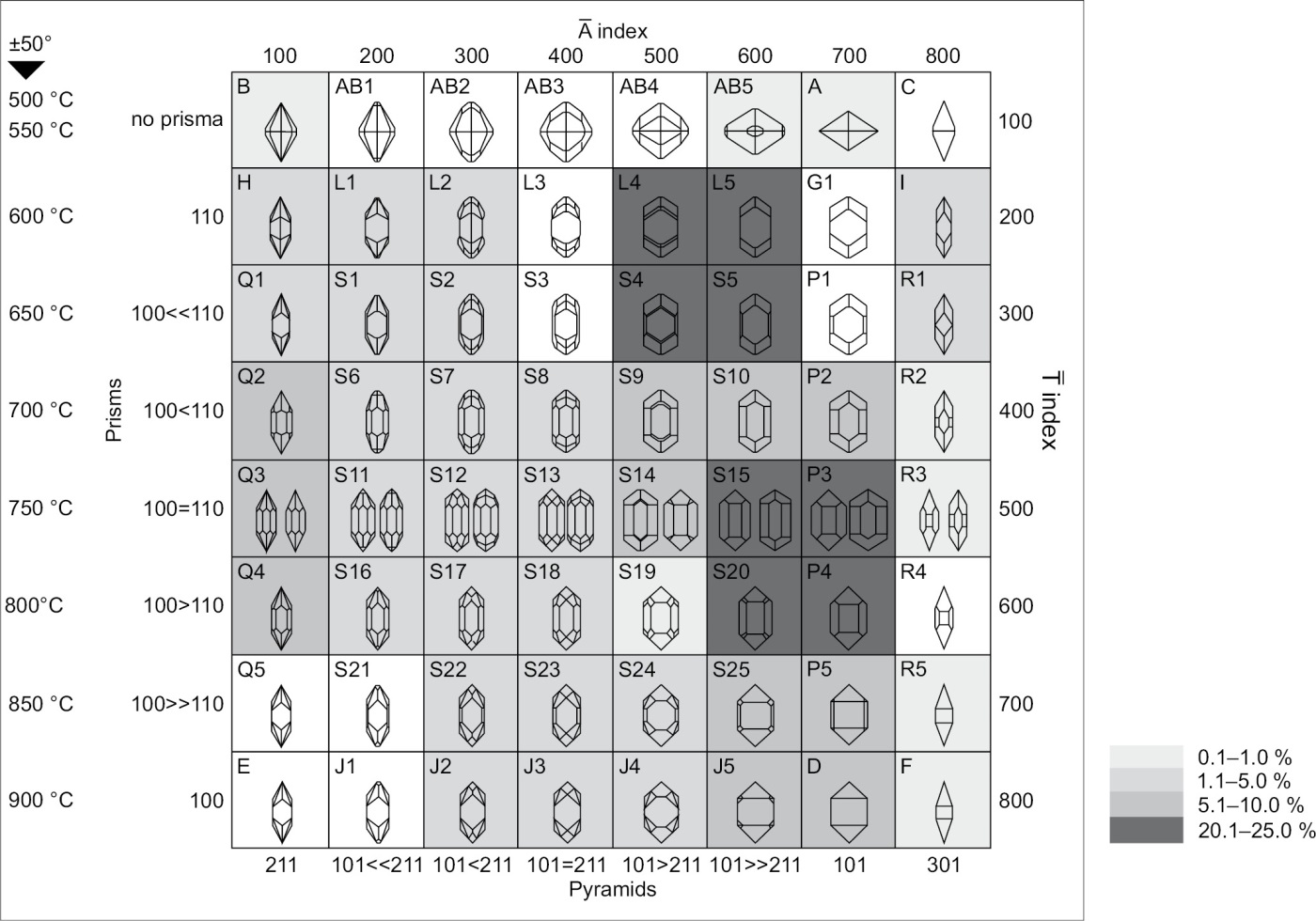

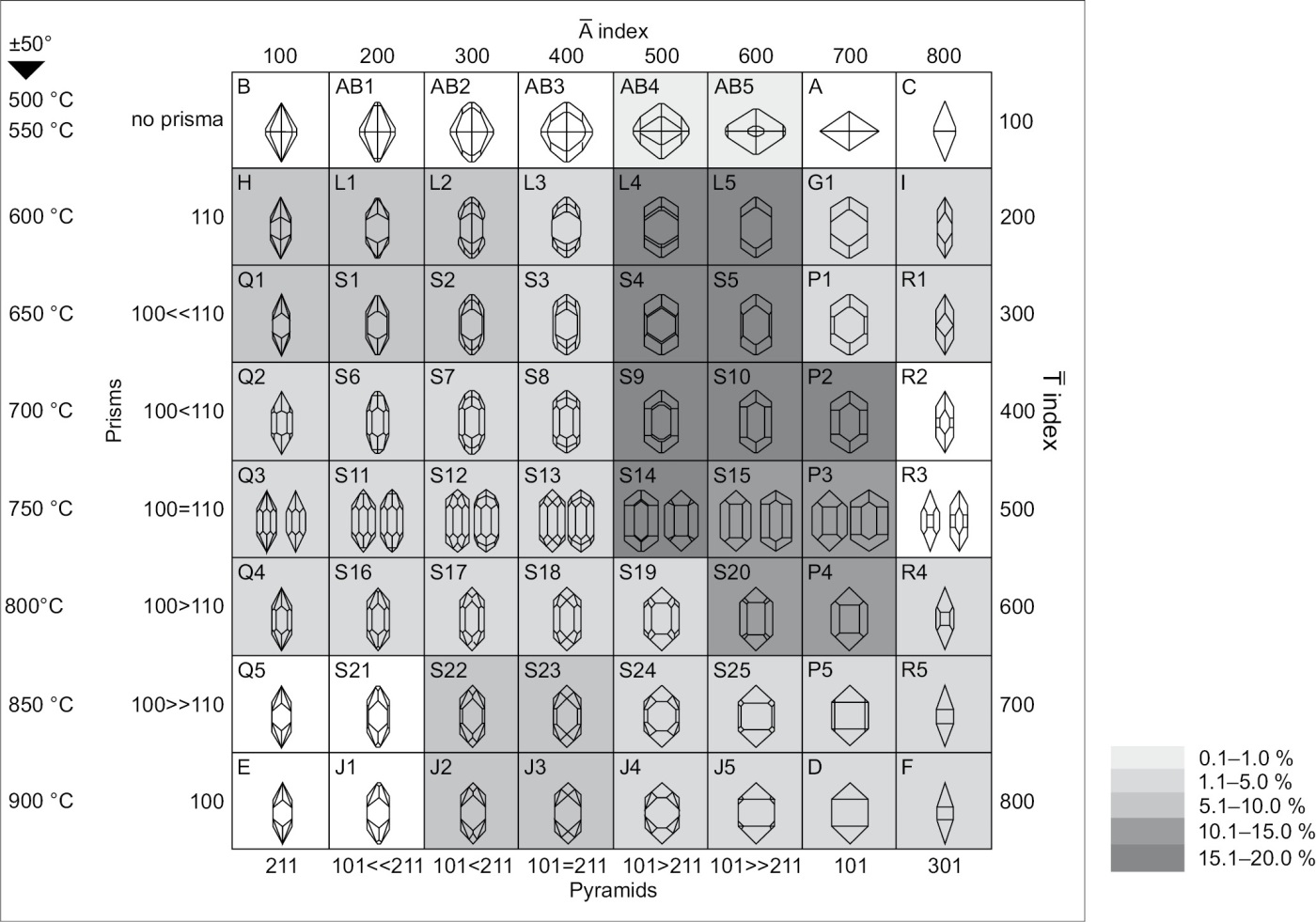

The analysis of detrital zircon morphology [Pupin, 1980; Belousova et al., 2006] indicates that subalkaline (calc-alkaline) granitoids played a key role in the formation of the Western Kamchatka Basin in the Eocene, with an insignificant participation of high-aluminous muscovite-bearing granites (App. 2, Table 2.1; Fig. 2.1, 2.2).

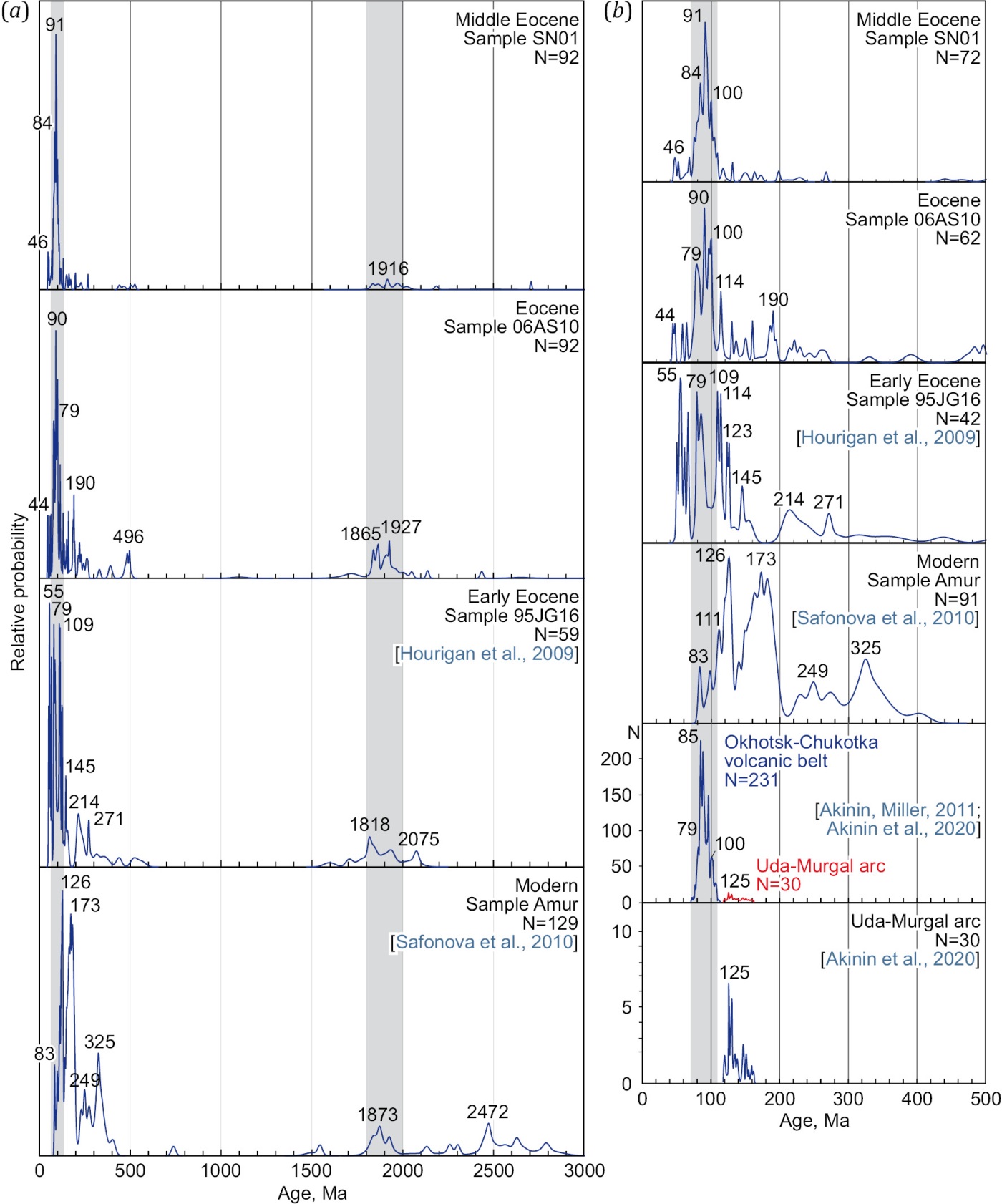

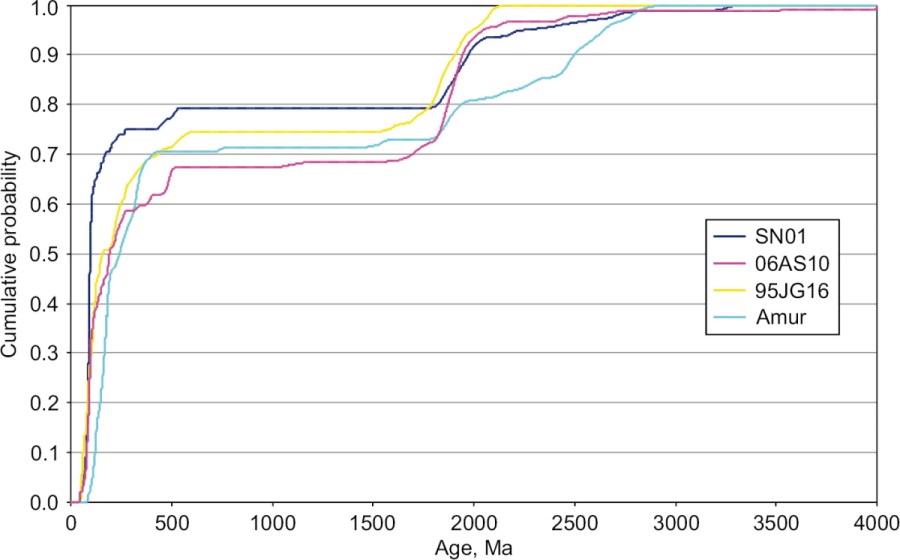

Detrital zircons from two sandstone samples were dated by the LA-ICP-MS method at the Arizona LaserChron Center (100 single grain ages per sample). Sample locations are listed in Table 1, description of analytical methods is given in App. 3, measured isotopic ratios and interpreted ages and Concordia diagrams are presented in Suppl. 1 (see article page online). The U-Pb ages from each sample are plotted on relative age probability distribution diagrams [Ludwig, 2008] in Fig. 6. The relative age probability distribution diagrams for detrital grains younger than 500 Ma provide a more detailed comparison of the younger populations of zircons in the samples (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Comparison of the ages of the detrital zircons from the Sea of Okhotsk region based on age probability plots: 0–3000 Ma (a), 0–500 (b). See text for details.

Рис. 6. Сравнение распределения значений возраста обломочного циркона по образцам из Охотоморского региона на основе графиков плотности вероятности: 0–3000 млн лет (a), 0–500 млн лет (b). Подробности см. в тексте.

Grain U-Pb ages of detrital zircons are scarce for the Sea of Okhotsk region. A lone detrital zircon dataset is published for the Early Eocene sample (95JG16) from the Ukelayat Basin [Reiners et al., 2005; Hourigan et al., 2009]. Detrital zircon in modern sand (sample Amur) of the Amur River [Safonova et al., 2010] is used for comparison as "fingerprint" of the intracontinetal zircon provenance in northeast Russia. Finally, a compilation of ⁴⁰Ar/³⁹Ar and U/Pb SHRIMP ages for the Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt [Akinin, Miller, 2011; Akinin et al., 2020, 2022] is useful for characterization of the expected zircon age range for arc-derived detritus.

All of the samples from the Sea of Okhotsk region have a few Archean grains, but the age distributions have a significant percentage of 2.0–1.8 Ga zircons (14–24 % of the populations). The Amur sample alone has 8 % of 2.0–1.8 Ga zircons. The presence of the Early Proterozoic zircons indicates that the source region likely included the Siberian Craton, which shows a peak in magmatic activity at 1900 Ma [Rosen, 2002]. In the Sea of Okhotsk region there are the Avekova, the Okhotsk and the Omolon cratonal terranes [Nokleberg et al., 2001]. The Okhotsk and the Omolon terranes are interpreted as those derived from the North Asian (Siberian) Craton [Nokleberg et al., 2001]. The 1.9–1.8 Ga old zircons occur in metamorphic and migmatitic rocks of the Okhotsk [Kuz’min et al., 2009], Omolon and Avekova [Khanchuk, 2006] terranes. The recent study confirms the global episode of crust formation at 2.0–1.8 Ga, which gave rise to the Columbia supercontinent [Safonova et al., 2010].

The Paleozoic zircons are not present in significant abundance in the studied deposits. The Middle Eocene sample (06AS10) exhibits a small peak (3 % of the population) at ~500 Ma. The Late Paleozoic – Early Mesozoic zircons (~400–215 Ma) in the modern Amur sand could be derived from the Mongol-Okhotsk orogen [Safonova et al., 2010].

A set of ages, spanning the Mesozoic and Cenozoic (~250–45 Ma), is the most abundant zircon age population (~52–74 %). The zircons older than 110 Ma are present in large percentages (~47 %) only in the Amur sample, but samples from the northern part of the Sea of Okhotsk region contain much less zircons (~10–25 %) of this age (~250–110 Ma). The northeast margin of Russia is characterized by the occurrence of long-term island arc and continental arc magmatism that can account for the observed Mesozoic zircon ages [Khanchuk, 2006; Miller et al., 2002; Khanchuk et al., 2025]. The peak (~110–77 Ma) is significant in all samples (~22–54 %) with exemption of the Amur sample (5 %) (Fig. 6). The Okhotsk-Chukotka Volcanic Belt (OCVB) was active from about 106 to 77 Ma [Akinin, Miller, 2011; Tikhomirov et al., 2012]. In particular, the Cretaceous grain-ages can be related to the OCVB formation sources.

Both scattered volcanic rocks in the Koryak Highlands [Ledneva, Matukov, 2009] and volcanic belt in the Western Kamchatka (see Fig. 2, kk – overlapping magmatic arc) show the early Cenozoic activity. These sources may account for the zircons younger than 77 Ma. The Early Eocene zircons (~55 Ma) are typical for the sample (95JG16) from the Ukelayat Basin [Hourigan et al., 2009]. Four grains from the sandstones of the Western Kamchatka Basin date back to the Middle Eocene (~48–44 Ma). The Kinkil (Western Kamchatka) volcanic belt was active contemporaneously with deposition in Western Kamchatka Basin in the Middle Eocene.

6. INTERPRETATIONS

The study of the sandstones sampled near the base of the Western Kamchatka Basin suggests that the provenance for the sandstones is mainly associated with orogen recycling in magmatic arcs (see Fig. 5) [Dickinson, 1985]. The analysis of heavy minerals indicates a mixture of mafic and sialic materials. The only possible provenance for sialic material is the terranes of northeastern Asian margin and the Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt built on these terranes (see Fig. 2). This conclusion is supported by the north-northeast paleocurrent directions [Khisamutdinova et al., 2016]. On the one hand, the mafic clastics from the east were probably derived from the Olyutorka-Kamchatka ensimatic island-arc collided with continental margin in the Eocene. On the other hand, the mafic terranes of Asian margin could shed off sediments towards the Western Kamchatka Basin from the west.

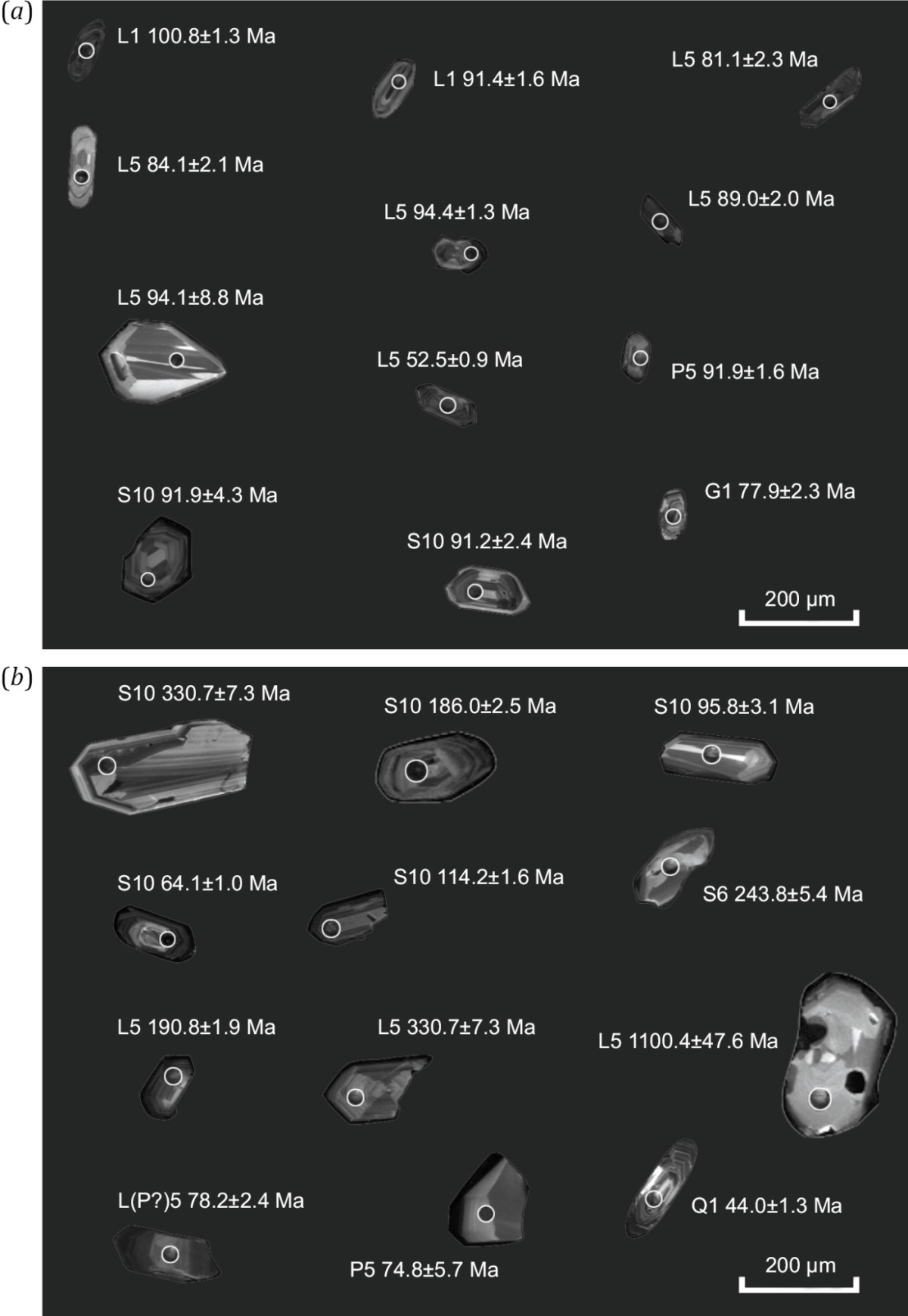

The morphology of detrital zircons indicates that the dominant provenance of the Eocene subalkaline (calc-alkaline) granitoids was the Western Kamchatka Basin with a small amount of high-aluminous muscovite granites. We correlate the morphologies of detrital grains, observed in CL-images, with ages of zircons (Fig. 7). The crystals with morphologies L5 and S10 are typical for subalkaline (calc-alkaline) and alkaline granitoids and have ages similar to the OCVB age (Fig. 7, a, sample SN01). Some crystals exhibit elongation attributed to volcanic sources, for example, L5 – 84.1±2.1 Ma, L5 – 81.1±2.3 Ma (Fig. 7, a). Sample 06AS10 contains zircons with a larger age difference (Fig. 7, b). The crystal (Q1 – 44.0±1.3) is definitely related to the Kinkil (Western Kamchatka) volcanic belt.

Fig. 7. Correlation of morphology of detrital zircons on the CL-image with ages. (a) – sample SN01, (b) – sample 06AS10.

Рис. 7. Сопоставление морфологии обломочных цирконов на CL-изображениях с возрастом: (a) – образец SN01, (b) – образец 06AS10.

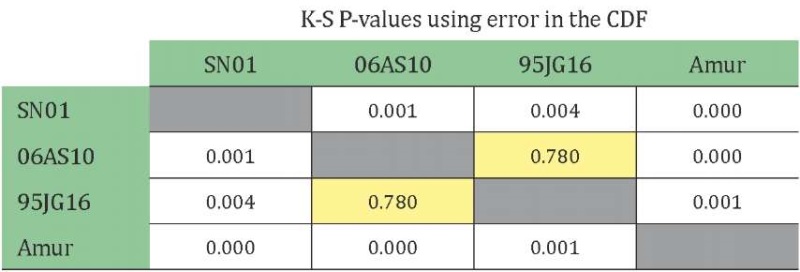

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistical test was used to further assess the similarity of distributions of the U/Pb LA-ICP-MS ages of single grains, with the results presented in Table 2 (Fig. 8). According the K-S test, the sample from the modern Amur sand is different from other samples. The distributions of the detrital zircon ages are similar in samples 95JG16 and 06AS10. It is an unusual and important observation because sample 95JG16 was collected from the forearc sediments deposited before the arc-continent collision event in the Middle Eocene [Soloviev et al., 2002]. Sandstone sample 06AS10 has been taken near the base of the Western Kamchatka Basin. The sedimentation in this basin started after the collision of the Olyutorka-Kamchatka island-arc terrane with northeastern Asian margin. The new detrital zircon data allow us to speculate that depositional system along the northern Kamchatka segment of the Asian margin was not dramatically affected by arc-continent collision, because collision in this area occurred at a low crustal level, and the suture is only shallowly exposed (~3–4 km) [Shapiro et al., 2008; Soloviev, Garver, 2012]. The difference between samples 06AS10 and SN01 could be explained by their stratigraphic positions (see Fig. 4) and provenance evolution up the section. The sources were more various in the beginning of sedimentation in the Western Kamchatka Basin and similar to deposition in the preexisting forearc basin. The provenance is becoming more uniform up the section, and the OCVB starts to dominate as a source for clastics (see Fig. 6, sample SN01).

Table 2. K-S test results for samples from the Sea of Okhotsk region

Таблица 2. Результаты K-S теста для образцов из Охотоморского региона

Note. The data are presented for sample 95JG16 [Reiners et al., 2005; Hourigan et al., 2009] and for sample Amur [Safonova et al., 2010]. The K-S test is a non-parametric method for comparing cumulative probability distributions. P(KS) gives the probability that random chance alone might produce the observed difference in two distributions derived from the same parent population. A low test probability, such as P(KS)<0.05, would indicate that the differences between the two distributions are significant and that the samples are not similar in terms of their age population. If P(KS)>>0.05, then the differences are just a factor of random chance. To apply the K-S test to the data, we used the algorithm from [Guynn, Gehrels, 2010]. Values that pass the K–S test at 95 % confidence level and not rejected are shown in yellow.

Примечание. Приведены данные для образцов 95JG16 [Reiners et al., 2005; Hourigan et al., 2009] и Амур [Safonova et al., 2010]. Тест Колмогорова–Смирнова представляет собой непараметрический тест, применяемый для сравнения кумулятивного распределения вероятностей. Значению P(KS) соответствует вероятность того, что уже сама случайность может быть причиной различия двух распределений, выведенных из одной и той же исходной совокупности. Низкая вероятность теста при P(KS)<0.05, будет означать, что разница двух распределений существенна, и что образцы не являются однородными с точки зрения возрастного состава популяции. Если же P(KS)>>0.05, то различие является просто фактором случайности. Для применения теста Колмогорова-Смирнова к данным мы использовали алгоритм, приведенный в работе [Guynn, Gehrels, 2010]. Значения, прошедшие тест Колмогорова – Смирнова при уровне доверительной вероятности 95 % и не попавшие в выбраковку, показаны желтым цветом.

Fig. 8. Comparison of detrital ages distributions in samples from the Sea of Okhotsk region based on the cumulative age probability plot.

Рис. 8. Сравнение распределения значений возраста обломочного циркона в образцах из Охотоморского региона на кумулятивном графике вероятности возраста.

Thereby, new data allow us to prove that sedimentation in the Western Kamchatka Basin started in the Eocene, and the Okhotsk-Chukotka vocanic belt, terranes of the northeastern Asian margin and the Olyutorka-Kamchatka island-arc terrane shed off clastic material towards this basin. We can speculate that the Paleo-Penzhina River system has already existed in the Eocene.

7. CONCLUSIONS

The study of the sandstones near the base of the Western Kamchatka Basin suggests that the provenance for the sandstones is mainly associated with orogen recycling in magmatic arcs. The presence of rutile, black spinel, anatase and pyroxene in heavy fraction may indicate the erosion of basic rocks; the prevalence of these minerals also indicates a significant effect of the source. The mafic terranes of the Asian margin on the west or/and the Olyutorka-Kamchatka ensimatic island arc supply the basic material to the Western Kamchatka Basin in the Eocene. By the presence of zircon and apatite, we can also suggest the existence of granitoids in the area of erosion. The provenances of the sialic clasts were continental blocks in Asian margin and the Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt. The existence of the sialic sources in the Eocene allows us to assume the possibility of finding the good quality collectors in the Eocene deposits of the Western Kamchatka Basin in the north of the Sea of Okhotsk.

According to the analysis of the morphology of zircon we can make the following conclusion: subalkaline (calc-alkaline) granitoids with a small proportion of high-aluminous muscovite granites are dominant in provenances for the Western Kamchatka Basin in the Eocene. This conclusion is consistent with the results of dating of detrital zircons from sediments of the Western Kamchatka Basin. The Eocene deposits contain detrital zircons whose ages are similar to the age of the Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt, which is known for large amounts of calc-alkaline igneous rocks, including contaminated mantle-crust granitoids [Akinin, Milller, 2011].

Most of the clastic material was transported from the north and northeast. The erosion of the Okhotsk-Chukotka belt had a significant influence on the Eocene sedimentation, where the longitudinal clastic material transport dominated over the transfer across the main strike of the structures. Thus, we can assume that the Paleo-Penzhina River system has already existed in the Eocene, and, perhaps, even earlier after the formation of the Okhotsk-Chukotka volcanic belt.

8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to A.A. Galaktionov and R.G. Chinakaev (PetroKamchatka Ltd), and D.M. Olshanetsky, A.V. Moiseev and T.N. Palechek (Geological Institute of RAS) for their assistance in doing fieldwork. We also acknowledge fruitful discussions and technical support from G. Gehrels (University of Arizona, USA), E.L. Miller (Stanford University, USA), E.V. Gorchilina (Geological Institute of RAS). We acknowledge constructive reviews from Olga Bergal-Kuvikas (Institute of volcanology and seismology FEB RAS) and anonymous.

9. CONTRIBUTION OF THE AUTHORS

All authors made an equivalent contribution to this article, read and approved the final manuscript.

10. DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

APPENDIX 1

Table 1.1. Composition of the Eocene sandstones from Western Kamchatka

Таблица 1.1. Состав эоценовых песчаников Западной Камчатки

|

Sample |

Qm |

Qp |

|

P |

Lvl |

Lvm |

Lvf |

Lvv |

Lm |

Lssh |

Lsa |

Lss |

Lsch |

Lst |

Lso |

Op |

nOp |

U |

T |

Mtx |

Aut |

|

Lv |

Ls |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

95JG-16 |

52 |

7 |

4 |

62 |

9 |

12 |

28 |

17 |

6 |

2 |

56 |

6 |

4 |

17 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

300 |

125 |

6 |

|

ХА-08-106 |

64 |

30 |

21 |

65 |

34 |

12 |

17 |

30 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

300 |

78 |

6 |

|

ХА08-99 |

62 |

41 |

10 |

57 |

21 |

9 |

25 |

41 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

12 |

300 |

120 |

14 |

|

SN-01 |

60 |

22 |

5 |

26 |

10 |

4 |

5 |

30 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

200 |

51 |

11 |

|

ХА08-69 |

70 |

37 |

7 |

67 |

17 |

4 |

26 |

34 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

3 |

10 |

300 |

96 |

17 |

|

ХА08-81 |

71 |

24 |

30 |

55 |

12 |

25 |

23 |

21 |

12 |

6 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

4 |

7 |

300 |

104 |

4 |

|

ХА08-86 |

70 |

38 |

15 |

48 |

15 |

23 |

26 |

24 |

7 |

12 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

2 |

9 |

300 |

130 |

25 |

|

ХА08-60 |

38 |

20 |

2 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

100 |

150 |

7 |

|

AS-06-10 |

57 |

16 |

10 |

20 |

16 |

2 |

18 |

28 |

10 |

4 |

0 |

8 |

19 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

200 |

63 |

17 |

|

06AS-09 |

74 |

31 |

43 |

56 |

15 |

17 |

34 |

10 |

1 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

8 |

300 |

98 |

5 |

|

06AS-08 |

69 |

41 |

37 |

48 |

13 |

19 |

27 |

15 |

2 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

12 |

300 |

108 |

8 |

Note. Qm – monocrystalline quartz; Qp – polycrystalline quartz; Qq – quartzites of unclear origin; P – feldspar; fragments of fine-grained rocks: Lv – volcanics, Lvl – volcanics with the lath texture (mainly mafic and intermediate), Lvm – rocks with the microlitic texture (mainly andesite, dacite, and their analogues), Lvf – acid rocks with the felsitic texture, Lvv – recrystallized glass barren of microlites, Lm – metamorphic rocks (including metaquartzites), Ls – sedimentary rocks, Lssh – shales, Lsa – argillite and aleuropelite, Lss – siltstone and fine-grained sandstone, Lsch – cherts, Lst – tuff, tuffogene silicilith, and tuffogene argillites, Lso – other sedimentary rocks (carbonate, coal), Op – ore minerals, nOp – colored minerals, U – undetermined rock fragments; T – total number of determinations of grain composition in thin section, Mtx – matrix and cement, Aut – authigenic minerals.

Примечание. Qm – монокристаллический кварц; Qp – поликристаллический кварц; Qq – кварциты неясного происхождения; P – полевой шпат; фрагменты мелкозернистых пород: Lv – вулканиты, Lvl – вулканиты с лейстовидной текстурой (главным образом основного и промежуточного состава), Lvm – породы с микролитической текстурой (в основном андезиты, дациты и их аналоги), Lvf – кислые породы с фельзитовой текстурой, Lvv – рекристаллизованное стекло и микролиты, Lm – метаморфические породы (включая метакварциты), Ls – осадочные породы, Lssh – сланцы, Lsa – аргиллит и алевропелит, Lss – алевролит и мелкозернистый песчаник, Lsch – че́рты, Lst – туфф, туфогенный силицилит, а также туфогенные аргиллиты, Lso – прочие осадочные породы (карбонат, уголь), Op – рудные минералы, nOp – цветные минералы, U – фрагменты неизвестной породы; T – общее число определений гранулометрического состава в шлифе, Mtx – матрица и цемент, Aut – аутигенные минералы.

Table 1.2. Percentage of rock-forming minerals in Eocene sandstones of Western Kamchatka

Таблица 1.2. Процентное соотношение породообразующих минералов эоценовых песчаников Западной Камчатки

|

Sample |

T |

Q, % |

F, % |

L, % |

L (vms) |

V, % |

M, % |

S, % |

V(lmf) |

Vl, % |

Vm, % |

Vf, % |

Mtx, % |

|

AS-06-10 |

200 |

37 |

10 |

53 |

94 |

63 |

11 |

26 |

33 |

48 |

6 |

46 |

24 |

|

SN-01 |

200 |

43 |

13 |

44 |

79 |

62 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

53 |

21 |

26 |

20 |

|

ХА-08-106 |

300 |

33 |

23 |

44 |

108 |

86 |

0 |

14 |

63 |

54 |

19 |

27 |

21 |

|

ХА08-99 |

300 |

37 |

20 |

43 |

111 |

86 |

2 |

12 |

55 |

38 |

16 |

46 |

29 |

|

ХА08-69 |

300 |

38 |

24 |

38 |

98 |

83 |

0 |

17 |

47 |

36 |

9 |

55 |

24 |

|

ХА08-81 |

300 |

34 |

19 |

47 |

104 |

78 |

12 |

10 |

60 |

20 |

42 |

38 |

26 |

|

ХА08-86 |

300 |

38 |

17 |

45 |

111 |

79 |

6 |

15 |

64 |

23 |

36 |

41 |

30 |

|

ХА08-60 |

100 |

64 |

28 |

8 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

– |

– |

– |

60 |

|

06AS-09 |

300 |

37 |

19 |

44 |

84 |

90 |

1 |

9 |

66 |

23 |

26 |

51 |

25 |

|

06AS-08 |

300 |

39 |

17 |

44 |

85 |

87 |

2 |

11 |

59 |

22 |

32 |

46 |

26 |

|

95JG-16 |

300 |

21 |

12 |

58 |

160 |

41 |

4 |

55 |

49 |

18 |

24 |

58 |

29 |

Note. Total components values are calculated using the formulas: Q,%=(Qm+Qp)/T×100; F,%=P/T×100; L,%=(Qq+Lv+Lm+Ls)/T×100; L(vms)=Lv+Lm+Ls; V,%=Lv/Lvms×100; M,%=Lm/Lvms×100; S,%=Ls/ Lvms×100, V(lmf)=Lvl+Lvm+Lvs; Vl,%=Lvl/Vlmf×100, Vm,%=Lvm/Vlmf×100; Vf,%=Lvf/Vlmf×100; mtx,%=mtx/(mtx+T)×100.

Примечание. Суммарные значения компонентов рассчитываются по формулам: Q,%=(Qm+Qp)/T×100; F,%=P/T×100; L,%=(Qq+Lv+Lm+Ls)/T×100; L(vms)=Lv+Lm+Ls; V,%=Lv/Lvms×100; M,%=Lm/Lvms×100; S,%=Ls/Lvms×100, V(lmf)=Lvl+Lvm+Lvs; Vl,%=Lvl/Vlmf×100, Vm,%=Lvm/Vlmf×100; Vf,%=Lvf/Vlmf×100; mtx,%=mtx/(mtx+T)×100.

Table 1.3. Composition of heavy minerals of the Eocene sandstones (Western Kamchatka)

Таблица 1.3. Состав минералов тяжелой фракции в эоценовых песчаниках (Западная Камчатка)

|

Mineral |

Sample |

|||||||||

|

ХА-08-106 |

ХА-08-99 |

SN-01 |

ХА-08-69 |

ХА-08-81 |

ХА-08-86 |

ХА-08-60 |

AS-06-10 |

AS-06-09 |

AS-06-08 |

|

|

Zircon |

11 |

24 |

17 |

29 |

3 |

3 |

8 |

4 |

22 |

34 |

|

Apatite |

– |

2 |

m |

– |

– |

5 |

– |

1 |

m |

– |

|

Rutile |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

20 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

Anatase |

– |

m |

– |

– |

m |

m |

– |

m |

– |

m |

|

Tourmaline |

– |

m |

– |

– |

m |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

– |

|

Leucoxene |

26 |

39 |

– |

m |

24 |

1 |

– |

– |

29 |

15 |

|

Sulphide |

20 |

7 |

13 |

16 |

60 |

67 |

63 |

75 |

– |

14 |

|

Clinopyroxene |

– |

– |

1 |

36 |

– |

– |

m |

m |

– |

– |

|

Orthopyroxene |

– |

m |

2 |

– |

– |

m |

2 |

– |

– |

m |

|

Amphibole |

– |

– |

– |

– |

m |

– |

5 |

– |

m |

– |

|

Ilmenite |

10 |

– |

10 |

6 |

9 |

21 |

– |

– |

– |

4 |

|

Spinel |

17 |

15 |

12 |

7 |

m |

– |

m |

14 |

26 |

21 |

|

Garnet |

12 |

10 |

10 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

18 |

8 |

|

Black ore mineral |

– |

– |

33 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Note. m – single marks.

Примечание. m – единичные знаки.

APPENDIX 2

MORPHOLOGY OF THE DETRITAL ZIRCON

After the mineralogical analysis, zircon crystal morphology was analyzed using Pupin’s method [Pupin, 1980]. J.P. Pupin found the variability of zircon crystal forms depending on conditions in which granitoids are formed. It is found that chemical composition of the medium affects the growth and development of the pyramidal crystal faces, while temperature affects the prismatic faces. According to this, a classification has been proposed for the main types and subtypes of zircon forms depending on temperature (IT index) and alkali/alumina ratio in mineral-forming medium (index IA). The first one shows the rate of crystallization and presence of volatile components in the melt, the second one shows the heterogeneity of the medium and the evolution of its chemical composition [Pupin, 1980]. This method of the analysis of detrital zircons can also be used for the reconstruction of the features of the granitoids in granitoid provenance (for example, [Dunkl et al., 2001]). Based on the J.P. Pupin’s chart [Pupin, 1980], a typological chart was developed by [Belousova et al., 2006] classifying zircons by belonging to the type of granitoids. With the help of this chart it was determined which types of granitoids are eroded.

A fraction sized – 0.07 mm was used to analyze the morphology as the most representative from the point of preservation of the crystal forms of zircon. The counting was performed only among the euhedral grains. In average, for all the samples it was about 35 % for unrounded lightly colored and colorless euhedral crystals of different morphological type, which are valid for counting, about 45 % for half-rounded grains and about 20 % for rounded grains, so as the grains from detrital rocks were studied.

The initial classification of zircons [Pupin, 1980] was modified to make counting easier. Morphological types with a similar structure were grouped excluding elongation factor; each group was named by the leftmost morphological type from the classification (App. 2, Table 2.1, Fig. 2.1, 2.2). Counting was performed on 100–250 grains depending on the content of zircon in the sample. The result of the counting shows five morphological types of zircons dominating in the samples – H, L4, S9, S15, S25 (App. 2, Table 2.1, Fig. 2.1, 2.2). The content of other morphotypes of zircon is insignificant.

Let us consider which kind of rocks could supply the Eocene sedimentary basin with zircons of the predominant morphological types. According to the classification [Belousova et al., 2006], H-type zircons are common for high-aluminous muscovite-bearing S-type granites. L4-type zircons come from hybrid (contaminated) monzonites and alkali granites. S9 and S15-type zircons are typical for contaminated subalkaline and alkaline granites of I-type, including calc-alkaline subduction-related ones. S25-type zircons are common for alkaline granitoids and I-type tholeitic granites.

Thus, the morphology of detrital zircons indicates that subalkaline (calc-alkaline) granitoids were dominant in the provenance of the Western Kamchatka Basin in the Eocene, with a small amount of high-aluminous muscovite-bearing granites.

A large split of zircons (generally 1000–2000 grains) was incorporated into a 1" epoxy mount together with fragments of our Sri Lanka standard zircon. The mounts were sanded down to a depth of ~20 microns, polished, imaged, and cleaned prior to isotopic analysis.

U-Pb geochronology of zircons was conducted by laser ablation multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-MC-ICP-MS) in the Arizona LaserChron Center [Gehrels et al., 2006, 2008]. The analyses involve ablation of zircon with a New Wave UP193HE Excimer laser (operating at a wavelength of 193 nm) using a spot diameter of 30 microns. The ablated material is carried in helium into the plasma source of a Nu HR ICP-MS, which is equipped with a flight tube of sufficient width so that U, Th, and Pb isotopes are measured simultaneously. All measurements are made in static mode, using Faraday detectors with 3·10¹¹ Ohm resistors for ²³⁸U, ²³²Th, ²⁰⁸Pb/²⁰⁶Pb, and discrete dynode ion counters for ²⁰⁴Pb and ²⁰²Hg. Ion yields are ~0.8 mv per ppm. Each analysis consists of one 15-second integration on peaks with the laser off (for backgrounds), 15 one-second integrations with the laser firing, and a 30-second delay to purge the previous sample and prepare for the next analysis. The ablation pit is ~15 microns in depth.

For each analysis, the errors in determining ²⁰⁶Pb/²³⁸U and ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁴Pb result in a measurement error of ~1–2 % (at 2σ level) in the ²⁰⁶Pb/²³⁸U age. The errors in measurement of ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁷Pb and ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁴Pb also result in ~1–2% (at 2σ level) uncertainty in age for grains that are >1.0 Ga and substantially larger for younger grains due to low intensity of the ²⁰⁷Pb signal. For most analyses, the cross-over in precision of ²⁰⁶Pb/²³⁸U and ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁷Pb ages occurs at ~1.0 Ga.

²⁰⁴Hg interference with ²⁰⁴Pb is accounted for measurement of ²⁰²Hg during laser ablation and subtraction of ²⁰⁴Hg according to the natural ²⁰²Hg/²⁰⁴Hg of 4.35. This Hg correction is not significant for most of the analyses because our Hg backgrounds are low (generally ~150 cps at mass 204).

Common Pb correction is accomplished by using the Hg-corrected ²⁰⁴Pb and assuming an initial Pb composition from [Stacey, Kramers, 1975]. Uncertainties of 1.5 for ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁴Pb and 0.3 for ²⁰⁷Pb/²⁰⁴Pb are applied to these compositional values based on the variation in Pb isotopic composition in modern crystal rocks.

Inter-element fractionation of Pb/U is generally ~5 %, whereas apparent fractionation of Pb isotopes is generally <0.2 %. In-run analysis of fragments of a large zircon crystal (generally every fifth measurement) with the known age of 563.5±3.2 Ma (2σ error) is used to correct for this fractionation. The uncertainty resulting from the calibration correction is generally 1–2 % (2σ) for both ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁷Pb and ²⁰⁶Pb/²³⁸U ages.

Concentrations of U and Th are calibrated relative to our Sri Lanka zircon, which contains ~518 ppm of U and 68 ppm Th.

The analytical data are reported in Suppl. 1. The uncertainties shown in these tables are at the 1-sigma level and include only measurement errors. The analyses with >20 % discordancy (by comparison of ²⁰⁶Pb/²³⁸U and ²⁰⁶Pb/²⁰⁷Pb ages) or >5 % reverse discordancy are not included.

The resulting interpreted ages are shown on Pb*/U concordia diagrams and relative age-probability diagrams using the routines involved in Isoplot [Ludwig, 2008]. The age-probability diagrams show each age and its uncertainty (for measurement error only) as a normal distribution, and sum all ages from a sample into a single curve. Composite age probability plots are made from an in-house Excel program (available from www.geo.arizona.edu/alc) that normalizes each curve according to the number of constituent analyses so that each curve contains the same area and then stacks the probability curves.

Table 2.1. Contents of detrital zircons (%) of different morphological types [Pupin, 1980] in the Eocene sandstones from the Western Kamchatka

Таблица 2.1. Содержание зерен обломочного циркона (%) разных морфологических типов [Pupin, 1980] в эоценовых песчаниках Западной Камчатки

|

Sample |

Morphological type |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

B |

AB4 |

AB5 |

A |

H |

L1 |

L3 |

L4 |

G1 |

I |

Q2 |

S6 |

S7 |

S9 |

R2 |

S15 |

S19 |

R4 |

S22 |

S24 |

S25 |

R5 |

|

|

ХА08-106 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

7 |

2 |

27 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

1 |

17 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

13 |

0 |

|

ХА08-99 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

22 |

11 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

20 |

1 |

20 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

|

SN01 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

22 |

0 |

3 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

9 |

1 |

23 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

1 |

|

ХА08-69 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

2 |

1 |

14 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

22 |

2 |

11 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

14 |

3 |

|

ХА08-81 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

36 |

0 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

|

ХА08-86 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

6 |

1 |

25 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

15 |

1 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

0 |

|

06AS10 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

19 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

15 |

0 |

13 |

5 |

1 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

|

06AS09 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

2 |

3 |

23 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

18 |

0 |

9 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

|

06AS08 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

5 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

1 |

13 |

0 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

17 |

0 |

Note. The symbols of the morphological types correspond to domain joins: B=B, AB4=AB4, AB5=AB5, A=A, H=H+Q1, L1=L1+L2+S1+S2, L3=L3+S3, L4=L4+L5+S4+S5, G1=G1+P1, I=I+R1, Q2=Q2+Q3+Q4, S6=S6+S11, S7=S7+S8+S12+S13, S9=S9+S10+P2+S14, R2=R2+R3, S15=S15+P3+S20+P4, S19=S19, R4=R4, S22=S22+S23+J2+J3, S24=S24+J4, S25=S25+P5+J5+D, R5=R5+F. The dominating morphological types of zircons are highlighted in bold.

Примечание. Символы морфологических типов соответствуют присоединениям к доменам: B=B, AB4=AB4, AB5=AB5, A=A, H=H+Q1, L1=L1+L2+S1+S2, L3=L3+S3, L4=L4+L5+S4+S5, G1=G1+P1, I=I+R1, Q2=Q2+Q3+Q4, S6=S6+S11, S7=S7+S8+S12+S13, S9=S9+S10+P2+S14, R2=R2+R3, S15=S15+P3+S20+P4, S19=S19, R4=R4, S22=S22+S23+J2+J3, S24=S24+J4, S25=S25+P5+J5+D, R5=R5+F. Доминирующие морфологические типы цирконов выделены жирным шрифтом.

Fig. 2.1. The content of detrital zircons (%) of different morphology for sample SN01 is shown by colors (App. 2, Table 2.1). Zircon typological classification and corresponding geothermometric scale proposed by [Pupin, 1980]. Index A reflects the Al/alkali ratio, controlling the development of zircon pyramids, whereas temperature affects the development of different zircon prisms.

Рис. 2.1. Содержание детритового циркона (%) различной морфологии в образце SN01 показано в цвете (Прил. 2, Табл. 2.1). Типологическая классификация цирконов и соответствующая геотермометрическая шкала, предложенная в работе [Pupin, 1980]. Индекс A отражает соотношение алюминия и щелочей, контролирующее развитие пирамидальных простых форм, в то время как температура оказывает влияние на развитие призм.

Fig. 2.2. The content of detrital zircons (%) of different morphology for sample 06AS10 is shown by colors (App. 2, Table 2.1). Zircon typological classification and corresponding geothermometric scale proposed by [Pupin, 1980]. Index A reflects the Al/alkali ratio, controlling the development of zircon pyramids, whereas temperature affects the development of different zircon prisms.

Рис. 2.2. Содержание детритового циркона (%) различной морфологии в образце 06AS10 показано в цвете (Прил. 2, Табл. 2.1). Типологическая классификация цирконов и соответствующая геотермометрическая шкала, предложенная в работе [Pupin, 1980]. Индекс A отражает соотношение алюминия и щелочей, контролирующее развитие пирамидальных простых форм, в то время как температура оказывает влияние на развитие призм.

References

1. Akinin V.V., Miller E.L., 2011. The Evolution of the Calc-Alkalic Magmas of the Okhotsk-Chukotka Volcanic Belt. Petrology 19 (3), 237–277. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0869591111020020.

2. Akinin V.V., MIller E.L., Toro J., Prokopiev A., Gottlieb E.S., Pearcey S., Polzunenkov G.O., Trunilina V.A., 2020. Episodicity and the Dance of Late Mesozoic Magmatism and Deformation Along the Northern Circum-Pacific Margin: North-Eastern Russia to the Cordillera. Earth-Science Reviews 208, 103272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103272.

3. Akinin V.V., Smirnov V.N., Fedorov P.I., Polzunenkov G.O., Alekseev D.I., 2022. Paleogene Volcanism of North Okhotsk Region. Petrology 31 (1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0869591122010039.

4. Belonin M.D., Grigorenko Yu.N., Margulis L.S., Andieva T.A., Sobolev, V.S., Goma L.M., Fregatova N.A., Voronkov Yu.S., Pylina L.M., Brazhaev V.I., Zhukova L.I., 2003. Prospecting Potential of the Western Kamchatka and Adjacent Shelf (Oil and Gas). Nedra, Saint Petersburg, 120 p. (in Russian)

5. Belousova E.A., Griffin W.L., O’Reilly S.Y., 2006. Zircon Crystal Morphology, Trace Element Signatures and Hf Isotope Composition as a Tool for Petrogenetic Modelling: Examples from Eastern Australian Granitoids. Journal of Petrology 47 (2), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egi077.

6. Bogdanov N.A., Chekhovich V.D., 2002. On the Collision Between the West Kamchatka and Sea of Okhotsk Plates. Geotectonics 36 (1), 63–76.

7. Bogdanov N.A., Dobretsov N.L., 2002. The Okhotsk Volcanic Plateau. Russian Geology and Geophysics 43 (2), 87–99.

8. Dickinson W.D., 1985. Interpreting Provenance Relation from Detrital Modes. In: G.G. Zuffa (Ed.), Provenance of Arenites. Springer, Dordrecht, p. 333–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2809-6_15.

9. Dunkl I., Di Giulio A., Kuhlemann J., 2001. Combination of Single-Grain Fission-Track Chronology and Morphological Analysis of Detrital Zircon Crystals in Provenance Studies: Sources of the Macigno Formation (Apennines, Italy). Journal of Sedimentary Research 71 (4), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1306/102900710516.

10. Folk R.L., Andrews P.B., Lewis D.W., 1970. Detrital Sedimentary Rock Classification and Nomenclature for Use in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 13 (4), 937–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.1970.10418211.

11. Garver J.I., Soloviev A.V., Bullen M.E., Brandon M.T., 2000. Towards a More Complete Record of Magmatism and Exhumation in Continental Arcs, Using Detrital Fission-Track Thermochrometry. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part A: Solid Earth and Geodesy 25 (6–7), 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-1895(00)00086-7.

12. Gehrels G., Valencia V., Pullen A., 2006. Detrital Zircon Geochronology by Laser Ablation Multicollector ICPMS at the Arizona LaserChron Center. The Paleontological Society Papers 12, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1089332600001352.

13. Gehrels G.E., Valencia V., Ruiz J., 2008. Enhanced Precision, Accuracy, Efficiency, and Spatial Resolution of U-Pb Ages by Laser Ablation-Multicollector-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 9, Q03017. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GC001805.

14. Geological Map of the USSR, 1965. Western Kamchatka Series. Sheet O-57-XIX, XX. VSEGEI, Leningrad (in Russian) [Геологическая карта СССР. Западно-Камчатская серия. Лист О-57-XX, XIX. Л.: ВСЕГЕИ, 1965].

15. Gladenkov Yu.B., 1980. Stratigraphy of Marine Paleogene and Neogene of Northeast Asia (Chukotka, Kamchatka, Sakhalin). AAPG Bulletin 64 (7), 1087–1093. https://doi.org/10.1306/2F919436-16CE-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

16. Gladenkov Yu.B., Shantser A.E., Chelebayeva A.I., Sinel’nikova V.N., Antipov M.P., Ben’yamovskiy V.N., Brattseva G.M., Polyanskiy B.V., Stupin S.I., Fedorov P.I., 1997. Lower Paleogene of Western Kamchatka (Stratigraphy, Paleogeography, Geological Events). GEOS, Moscow, 367 p. (in Russian).

17. Guynn J., Gehrels G.E., 2010. Comparison of Detrital Zircon Age Distributions in the K-S Test. University of Arizona, Arizona LaserChron Center, Tucson, 16 p.

18. Harbert W., Sokolov S., Heiphetz A., 2003. Reconnaissance Hydrocarbon Geology of the Anadyrsky and Khatyrsky Cenozoic Sedimentary Basins, Northern Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia. AAPG Bulletin 87 (2), 183–195. DOI:10.1306/09030201082.

19. Hourigan J.K., 2003. Mesozoic-Cenozoic Tectonic and Magmatic Evolution of the Northeast Russian Margin. PhD Thesis (Doctor of Philosophy). Stanford, 234 p.

20. Hourigan J.K., Akinin V.V., 2004. Tectonic and Chronostratigraphic Implications of New 40Ar/39Ar Geochronology and Geochemistry of the Arman and Maltan-Ola Volcanic Fields, Okhotsk-Chukotka Volcanic Belt, Northeastern Russia. GSA Bulletin 116 (5–6), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1130/B25340.1.

21. Hourigan J.K., Brandon M.T., Soloviev A.V., Kirmasov A.B., Garver J.I., Stevenson J., Reiners P.W., 2009. Eocene Arc-Continent Collision and Crustal Consolidation in Kamchatka, Russian Far East. American Journal of Science 309 (5), 333–396. https://doi.org/10.2475/05.2009.01.

22. Kalinin D.F., Egorov A.S., Bol’shakova N.V., 2022. Oil and Gas Potential of the West Kamchatka Coast and Its Relation to the Structural and Tectonic Structure of the Sea of Okhotsk Region Based on Geophysical Data. Bulletin of Kamchatka Regional Association "Educational-Scientific Center". Earth Sciences 1 (53), 59–75 (in Russian) DOI:10.31431/1816-5524-2022-1-53-59-75.

23. Khanchuk A.I. (Ed.), 2006. Geodynamics, Magmatism and Metallogeny of the Eastern Regions of Russia. Book 1. Dal’nauka, Vladivostok, 572 p. (in Russian)

24. Khanchuk A.I., Emelyanova T.A., Vovna G.M., Savelyev Yu.O., Lee N.S., 2025. Cretaceous and Paleogene Granitoids of the Kashevarov Bank and the Origin of the Basement in the North of the Sea of Okhotsk. Russian Journal of Pacific Geology 19 (2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1819714024700635.

25. Kharakhinov V.V., 2010. Oil-and-Gas Geology of the Sakhalin Region. Moscow, Nauchny Mir, 275 p. (in Russian)

26. Khisamutdinova A.I., Soloviev A.V., Medvedeva L.V., 2018. Hydrocarbon Potential of Western Kamchatka. Mineral Recourses of Russia. Economics and Management 6, 11–16 (in Russian)

27. Khisamutdinova A.I., Solov'ev A.V., Rozhkova D.V., 2016. Provenance Analysis for Middle Eocene Sediments in the West Kamchatka Sedimentary Basin (Tigil Area). Lithology and Mineral Resources 51 (4), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0024490216040039.

28. Khvedchuk I.I., 1993. The Petroleum Basins of the Sea of Okhotsk. AAPG Bulletin 77 (9), 1637. DOI:10.1306/bdff81e6-1718-11d7-8645000102c1865d.

29. Konstantinovskaia E.A., 2001. Arc-Continent Collision and Subduction Reversal in the Cenozoic Evolution of the Northwest Pacific: An Example from Kamchatka (NE Russia). Tectonophysics 333 (1–2), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1951(00)00268-7.

30. Kuz’min V.K., Glebovitskii V.A., Rodionov N.V., Antonov A.V., Bogomolov E.S., Sergeev S.A., 2009. Main Formation Stages of the Paleoarchean Crustin the Kukhtui Inlier of the Okhotsk Massif. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 17 (4), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0869593809040017.

31. Ledneva G.V., Matukov D.I., 2009. Timing of Crystallization of Plutonic Rocks from the Kuyul Ophiolite Terrane (Koryak Highland): U-Pb Microprobe (SHRIMP) Zircon Dating. Doklady Earth Sciences 424 (1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028334X09010036.

32. Litvinov A.F., Patoka M.G., Markovskii B.A., 1999. Map of the Mineral Resources of Kamchatka Region. Scale of 1:500000. VSEGEI, Saint Petersburg (in Russian)

33. Ludwig K.R., 2008. ISOPLOT 3.6. A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel. User’s Manual. Berkeley Geochronology Center Special Publication 4, 77 p.

34. Mazarovich A.O., Soloviev A.V., Moiseev A.V., Ol’shanetskii D.M., Khisamutdinova A.I., 2010. Deformations in Tertiary Complexes of Western Kamchatka (Tochilo Section). Doklady Earth Sciences 433 (1), 851–855. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028334X10070019.

35. Mel’nikov P.N., Soloviev A.V., Akhmedsafin S.K., Rybal’chenko V.V., Kravchenko M.N., Ignatova V.A., Shpilman M.A., Grekova L.S. et al., 2022. Total Initial Onshore Hydrocarbon Resources of the Kamchatka Region: Updating the Quantitative Estimate. Oil and Gas Geology 4, 5–25 27 (in Russian) https://doi.org/10.31087/0016-7894-2022-4-5-25.

36. Miller E.L., Gelman M., Parfenov L., Hourigan J., 2002. Tectonic Setting of Mesozoic Magmatism: A Comparison Between Northeastern Russia and the North American Cordillera. In: E.L. Miller, A. Grantz, S.L. Klemperer (Eds), Tectonic Evolution of the Bering Shelf-Chukchi Sea-Arctic Margin and Adjacent Landmasses. GSA, p. 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1130/0-8137-2360-4.313.

37. Nokleberg W.J., Parfenov L.M., Monger J.W., Norton I.O., Khanchuk A.I., Stone D.B., Scotese C.R., Scholl D.W., Fujita K., 2001. Phanerozoic Tectonic Evolution of the Circum-North Pacific. USGS Professional Paper 1626. 122 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp1626.

38. Ogg J.G., Ogg G., Gradstein F.M., 2008. The Concise Geologic Time Scale. Cambridge University Press, 177 p.

39. Oleinik A.E., 2001. Eocene Gastropods of Western Kamchatka – Implications for High-Latitude North Pacific Biostratigraphy and Biogeography. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 166 (1–2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00205-4.

40. Parfenov L.M., Natal’in B.A., 1977. Mesozoic-Cenozoic Tectonic Evolution of Northeastern Asia. Doklady of the USSR Academy of Sciences 235 (2), 89–91 (in Russian)

41. Pettijohn F.J., 1975. Sedimentary Rocks. Harper and Row, New York, 628 p.

42. Pupin J.P., 1980. Zircon and Granite Petrology. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 73, 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00381441.

43. Reiners P.W., Campbell I.H., Nicolescu S., Allen C.M., Hourigan J.K., Garver J.I., Mattinson J.M., Cowan D.S., 2005. (U-Th)/(He-Pb) Double Dating of Detrital Zircons. American Journal of Science 305 (4), 259–311.

44. Rosen O.M., 2002. Siberian Craton – A Fragment of a Paleoproterozoic Supercontinent. Russian Journal of Earth Sciences 4 (2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.2205/2002ES000090.

45. Rozhdestvenskiy V.S., 1982. The Role of Wrench-Faults in the Structure of Sakhalin. Geotectonics 16 (4), 323–332.

46. Safonova I., Maruyama Sh., Hirata T., Kon Y., Rino Sh., 2010. LA ICP MS U-Pb Ages of Detrital Zircons from Russia Largest Rivers: Implications for Major Granitoid Events in Eurasia and Global Episodes of Supercontinent Formation. Journal of Geodynamics 50 (3–4), 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2010.02.008.

47. Schellart W.P., Jessell M.V., Lister G.S., 2003. Asymmetric Deformation in the Backarc Region of the Kuril Arc, Northwest Pacific: New Insights from Analogue Modeling. Tectonics 22 (5), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002TC001473.

48. Shapiro M.N., Soloviev A.V., 2009. Formation of the Olyutorsky-Kamchatka Foldbelt: A Kinematic Model. Russian Geology and Geophysics 50 (8), 668–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgg.2008.10.006.

49. Shapiro M.N., Soloviev A.V., Hourigan J.K., 2008. Lateral Structural Variability in Zone of Eocene Island-Arc–Continent Collision, Kamchatka. Geotectonics 42 (6), 469–487. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0016852108060046.

50. Soloviev A.V., Brandon M.T., Garver J.I., Shapiro M.N., 2001. Kinematics of the Vatyn-Lesnaya Thrust Fault (Southern Koryakia). Geotectonics 35 (6), 471–489.

51. Soloviev A.V., Garver J.I., 2012. Postcollision Exhumation of Northern Kamchatka Complexes (Lesnovskii Uplift). Doklady Earth Sciences 443 (1), 316–320. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028334X12030099.

52. Soloviev A.V., Garver J.I., Ledneva G.V., 2006. Accretionary Complex Related to Okhotsk-Chukotka Subduction, Omgon Range, Western Kamchatka, Russian Far East. Journal of Asian Earth Science 27 (4), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2005.04.009.

53. Soloviev A.V., Garver J.I., Shapiro M.N., Brandon M.T., Hourigan J.K., 2011. Eocene Arc-Continent Collision in Northern Kamchatka, Russian Far East. Russian Journal of Earth Science 12, ES1004. https://doi.org/10.2205/2011ES000504.

54. Soloviev A.V., Shapiro M.N., Garver J.I., Shcherbinina E.A., Kravchenko-Berezhnoy I.R., 2002. New Age Data from the Lesnaya Group: A Key to Understanding the Timing of Arc-Continent Collision, Kamchatka, Russia. Island Arc 11 (1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1738.2002.00353.x.

55. Stacey J.S., Kramers J.D., 1975. Approximation of Terrestrial Lead Isotope Evolution by a Two-Stage Model. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 26 (2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(75)90088-6.

56. Stoupakova A.V., Suslova A.A., Knipper A.A., Karnyushina E.E., Krylov O.V., Shelkov E.S., Korotkov S.B., Karnaukhov S.M., Osipova O.N., 2021. Features of the Geological Structure and Oil and Gas Content of the Shelves of the Far Eastern Seas. Georesources 23 (2), 26–34 (in Russian) https://doi.org/10.18599/grs.2021.2.2.

57. Tikhomirov P.L., Kalinina E.A., Moriguti T., Makishima A., Kobayashi K., Cherepanova I.Yu., Nakamura E., 2012. The Cretaceous Okhotsk-Chukotka Volcanic Belt (NE Russia): Geology, Geochronology, Magma Output Rates, and Implications on the Genesis of Silicic LIPs. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 221–222, 14–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.12.011.

58. Verzhbitsky V.E., Kononov M.V., 2006. Geodynamic Evolution of the Lithosphere of the Sea of Okhotsk Region from Geophysical Data. Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth 42 (6), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.745952.

59. Verzhbitsky V.E., Soloviev A.V., 2009. New Data on the Cenozoic Deformations of Western Kamchatka and Their Significance for the Recent Tectonics of Eastern Sea of Okhotsk Region. Oceanology 49 (4), 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0001437009040110.

60. Watson B.F., Fujita K., 1985. Tectonic Evolution of Kamchatka and the Sea of Okhotsk Implications for the Pacific Basin. In: D.G. Howell (Ed.), Tectonostratigraphic Terranes of the Circum-Pacific Region. Circum-Pacific Council for Energy and Mineral Resources, Houston, p. 333–348.

61. Worrall D.M., Kruglyak V., Kunst F., Kuznetsov V., 1996. Tertiary Tectonics of the Sea of Okhotsk, Russia: Far-Field Effects of the India-Eurasian Collision. Tectonics 15 (4), 813–826. https://doi.org/10.1029/95TC03684.

About the Authors

A. V. SolovievRussian Federation

Alexey V. Soloviev

36 Rte Entuziastov, Moscow 105118; , 7-1 Pyzhevsky Ln, Moscow 119017

A. I. Khisamutdinova

Russian Federation

7-1 Pyzhevsky Ln, Moscow 119017

J. K. Hourigan

United States

1156 High St, CA 95064, Santa Cruz

V. V. Akinin

Russian Federation

16 Portovaya St, Magadan 685000

D. V. Levochskaya

Russian Federation

18 Muravyova-Amursky St, Khabarovsk 680000

Supplementary files

|

1. Soloviev_et_al_2025_Suppl-1.xlsx | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(774KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

Review

For citations:

Soloviev A.V., Khisamutdinova A.I., Hourigan J.K., Akinin V.V., Levochskaya D.V. AGE AND COMPOSITION OF EOCENE SANDSTONES IN WESTERN KAMCHATKA: APPLICATION TO THE STUDY OF PROVENANCE FOR PETROLEUM RESERVOIRS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK. Geodynamics & Tectonophysics. 2025;16(5):0852. https://doi.org/10.5800/GT-2025-16-5-0852. EDN: falzbc